Al was once a committed, easy-going deputy's deputy. The 15-year law enforcement veteran always showed up for roll call 10 to 15 minutes early, worked overtime as needed, and accepted rotating shifts and assignments to any department division without complaint.

Most officers on the force wanted to work with Al. He could be counted on as backup, and would stick around at a scene while others investigated or did booking procedures. The physically fit officer was always the first through the door, be it a bar fight or a search warrant. He would write the big, complicated and boring reports. Citizens liked him too, often writing letters commending his performance.

But Al changed in the spring of 1982. His sergeant was the first to notice. He began arriving late, and his uniform, once all spit and polish, was in a disheveled state. His hair grew shaggy and unkempt, and his once excellent physical condition deteriorated. He developed a puffy look from drinking too much.

The biggest change, however, was in Al's attitude. His temper, cocked on a hair trigger, could go off at the slightest provocation. He was always snapping at others or making snide remarks during briefings. Citizens began to notice. Al had worked 15 years without a complaint, but in a single month he had four.

As the above example illustrates, those likely to experience burnout are often those officers who were initially most committed. An officer cannot burnout if he or she has never been on fire.

The road to burnout is a long and lonely stretch. As illustrated above, it does not happen overnight. It is not a condition caused by one or two incidents, nor is it unique to certain personality types. It is a road traveled at one time or another by most law enforcement professionals, often midway through their career. That's the bad news. The good news is that it's possible to avoid burnout with proper maintenance, and if it does cause delays, repairs are cheap.

What causes burnout?The hectic life of the law enforcement professional causes burnout. The constant demands and the immense stress associated with cop work all contribute. Over time, these stressors eat up resources.

Consider the following example: An officer responds to a domestic disturbance within a large apartment complex. Upon her arrival, several children demand to see her patrol vehicle. A tenant wants to report a theft while another reports illegal drug use. When the officer finally arrives at the apartment, the male half of the domestic relates nothing is wrong. The female half wants her husband arrested for sleeping. Fortunately, no crime was committed, just a lot of bickering and marital discord. The officer, after calming the situation, departs the apartment, and again encounters a tenant. This tenant, obviously anti-establishment, calls the officer several names. A child runs to the officer stating she is lost. After locating the lost child's apartment and explaining child neglect to a worried mother, the officer finally gets to her patrol vehicle, ready to clear. To her dismay, she discovers she has locked her keys in the vehicle. Notifying dispatch of her predicament, she waits for the sergeant who has the master key. She knows she will be laughed at during the next roll call.

This officer continues her shift, answering similar multi-tasked calls, and for the next 15 years, she does this nearly every day. Finally the day-to-day demands, hectic situations and an uncooperative public trap her in a mysterious routine. Hopelessness sets in and finally, she runs out of gas, emotionally drained. This officer has traversed burnout road.

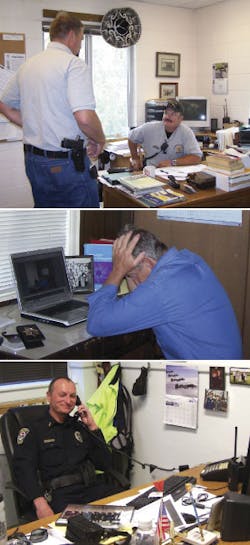

Signs and symptomsJob burnout is a physical and mental state caused by severe strain placed on the body until all resources are consumed. The symptoms of burnout develop gradually, and differ from person to person. But all sufferers have one symptom in common: fatigue. Burnt-out officers may not notice any problems and may consider their feelings normal. Often they cannot remember not feeling stressed, fatigued and physically tired all the time.

As their hectic lifestyle continues, more fatigue sets in. The exhausted officers may become anti-social, lose motivation, experience trouble concentrating, develop poor work habits and produce inferior work. These weary individuals begin to use more sick time because they are sick more often. A cold, which in healthy individuals lasts about a week, now lasts a month because they are rundown. Ulcers, indigestion and body aches are common. Depression may set in.

As burnout continues, officers who once stood straight and tall may slouch and lose concern for their physical appearance. Their hair and clothing may be unkempt, and their level of fitness may deteriorate.

Burnt-out officers may exhibit attitude problems. They may lose their desire to do positive deeds. They may begin to dislike talking to citizens and dread service calls. They may make snide remarks to other officers, become surly, and seldom provide input into important conversations.

Exhausted officers may also develop drug or alcohol problems. Eating disorders may arise, and problems with family and friends away from work may also unfold.

Burnout preventionThe best prevention for burnout is a knowledgeable manager. Police managers who know their people, both professionally and personally, can detect subtle personality changes that signal a problem.

But knowing every officer as an individual may be an insurmountable task, especially in larger departments. The best way to overcome this reality is to rely on a team concept. A strong team overcomes "blue silence" by taking care of each other. A cohesive team has open discussions about everything from performance to family issues.

It is the manager's responsibility to educate team members about the signs and symptoms of burnout, but it is each and every team member's responsibility to do something positive when signs and symptoms point to a problem. Just as a team member provides backup when entering a dark warehouse in the middle of the night, he or she must also learn to provide backup when the everyday stress of the job begins to wear on other team members.

Waging war on burnoutOnce burnout sets in, the same remedies designed to prevent it will also work to fight it. Managers and officers should familiarize themselves with prevention and treatment strategies, which include:

- Keeping the body healthy. Develop good eating habits. While fast foods provide a convenient meal, managers should encourage healthy choices. Stopping at the local donut shop for a cup of coffee and a donut for breakfast, grabbing a burger through the drive-through window or eating at the quick-mart for lunch contributes to burnout and takes away from an officer's performance.

- Staying fit. Exercise not only prepares an officer for emergencies, but it is also a strong weapon against burnout. Regular workouts, both aerobic and weight training, keep the body fit. Fit officers are physically able to contribute substantially to their community.

- Watching those work hours. The old saying, "too much work makes for a dull employee," fits. Individual employees, team members, managers and executive officers need to set limits.

- Talking about it. Communication is everything. Conversations with the affected officer can do wonders. Managers must bring the issue of burnout into the open and discuss life changes, performance issues and other causes for deterioration with officers. A climate of trust must be built to allow for forthright and honest communication. And while the affected officer might resist, managers must persist.

- Varying assignments. A change in assignments, rotating shifts or the addition of temporary duties often prevents burnout. New experiences, challenges and dimensions can serve to motivate those on the verge of burnout. However, be careful when adding duties. One cause of burnout is overconsumption, so it's important to be sure temporary additional duties are just that: Temporary.

- Encouraging time off. A strong family relationship eases the burnout battle. Don't let officers accumulate excessive vacation time. Managers should encourage vacations and days off, and if necessary, assign sick leave to those hard-headed individuals who exhibit the signs of burnout but refuse to acknowledge the problem.

- Accentuating the positive. Many organizations contribute to burnout through unintentional attitudes — worry and stress also flow downhill. A little smile from the top, a thank you for a good job, and commendations for outstanding performance all contribute toward preventing burnout.

- Officers headed toward burnout can be headed off at the pass before they take this long and lonely road. But it requires a concerned manager who pays attention and takes the time to educate his entire team about burnout and how it can be prevented.

Jerry Carlton is a retired lieutenant from the Nevada Department of Public Safety. The graduate of the University of Louisville Southern Police Institute currently resides in the Pacific Northwest, and when not enjoying the outdoor life, fills his time freelance writing.

Jerry Carlton

Jerry Carlton is a retired lieutenant from the Nevada Department of Public Safety. The graduate of the University of Louisville Southern Police Institute currently resides in the Pacific Northwest, and when not enjoying the outdoor life, fills his time freelance writing.