If your agency is responsible for serving arrest warrants, you may agree that the more methods you have in place to catch criminals and serve these, the greater your chances will be for success. Like fishing, the more hooks in the water, the higher the probability there is to catch more fish. Check out the latest tactic implemented at the Anne Arundel County Sheriff’s Office in Maryland to do just that.

The sheriff’s office receives approximately 1,000 new arrest warrants each month for a variety of felonies and misdemeanors. In a county just shy of 700,000 citizens and a growing opioid/heroin epidemic, these warrant numbers are steadily increasing. Knowing this, six years ago I came up with an idea to help tackle this problem. The idea was to put another shiny hook in the water and see how many criminals would bite.

The Warrant/Tax Refund Intercept law

In this line of work, most would agree drugs and money are the top motivators for criminals. If it’s not an addiction driving someone’s behavior, than greed is normally a close second. With those factors in mind, our most recent creative tactic uses the power of the almighty dollar to fuel this one-of-a-kind law designed to serve arrest warrants—the Warrant/Tax Refund Intercept law.

The idea originated in 2011 when my chief deputy and I were walking to the State House in Annapolis on the opening day of the new legislative session. As we were walking over I mentioned how I was looking forward to a sizeable tax refund that year from both my federal and state tax returns. Then came the idea: what if the State Comptroller could withhold someone’s state tax return if they had an outstanding criminal arrest warrant against them? Then, once it was served or quashed by the courts, their tax refund would be released promptly.

I first pitched the idea to a member of the House of Delegates in 2011. I sold the idea to a delegate, a member of the Republican Party, who agreed to sponsor such legislation. The idea was crafted into the proper bill format and was assigned to committees in both the House and Senate. Needless to say, the bill landed in the toilet in year one. In fact, it never made it out of the respective committees for discussion, not to mention a vote for passage.

The next year, however, the exact same concept was drafted into a bill and sponsored by a delegate and senator who were Democrats, and I was called upon to present the idea before the county’s delegates and senators.

One of the biggest questions from the delegation was “How many ‘wanted’ people actually had jobs and were due tax refunds?” Many figured the majority of wanted people didn’t have legitimate jobs where they would need to file income taxes. In anticipation of this question I had some of my deputies ask 50 people they had arrested for an assortment of crimes, both felonies and misdemeanors, if they were expecting a state tax refund that year. Surprisingly, 40 percent of them were expecting tax refunds. Armed with that information, I reported the results to the elected officials and got their attention.

Another burning question: “What if taxes were filed jointly by a married couple and only one party was wanted?” Once again, in anticipation of this question, the State Comptroller’s Office previously indicated they were able to segregate a married couple’s refund and distribute a refund check accordingly to the non-wanted spouse. A minority of the delegation did not like this concept. They felt a household should not be punished if only one person in the marriage was wanted. Though I disagreed, I was well aware the delegation had the final say. Wanting badly for this bill to be endorsed, the art of compromise had to be practiced.

A number of concessions had to be made as this idea was beat to death. There were some who said the law should not apply to members of armed forces who had pending arrest warrants. Others did not think the law, if passed, should apply to juveniles. There were some who said the law should not apply to those parents in arrears in child support. Some thought the law should only pertain to those filing returns individually. With some concessions made, the Bill was drafted and distributed to both sides of the legislature as a one-year pilot.

Legislation calls for partnerships

As competent managers, we all know many successful operations happen by forming meaningful partnerships. This idea was no different. In fact, I needed the buy-in of a very important person—the Maryland State Comptroller, the Honorable Peter Franchot. Without his full support, the concept could never take place. The Comptroller fully endorsed the proposed idea. He committed his office to the task of matching the tax filer’s social security number and name, to the person named on the arrest warrant. Once that was accomplished he agreed to notify the wanted person in writing as to the status of their refund.

If and when the person’s warrant was taken care of, the Comptroller’s Office would release the tax return to the subject. Graciously, Franchot agreed to all these arduous tasks, including assigning his staff to develop software, whereas his systems could communicate with the application where the warrants were housed. This alone was no easy feat. Thanks to the support, commitment, research and testimony of Franchot and his staff, the bill became a valued law in Anne Arundel County in 2011 and produced impressive results in the following tax season.

Results-oriented

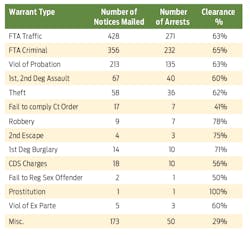

In the first three tax seasons of 2013, 2014 and 2015, 1,370 notices were mailed from the Office of the Comptroller for the State of Maryland to people wanted for crimes who were due state tax refunds. From those, 954 warrants were cleared as a result, amounting to a 70 percent clearance rate. Realizing many people have multiple warrants, this averaged to 300 times yearly my deputies didn’t have to hit the streets looking for someone. But what was especially appealing was the fact that 300 times a year wanted people came to the sheriff’s office instead of a deputy going to them. Any seasoned veteran in blue knows how rarely that happens.

At the conclusion of the third year, only 355 remained, which clearly showed the law was effective. In terms of money, during the same time $956,059 in tax refunds was held back due to outstanding warrants. By the end of the third year, only $175,869 remained because the wanted individuals took care of business in order to receive their refunds.

In the same three-year tax season it was interesting to see the number of actual arrests which occurred from the notices mailed. Some warrants were disposed of either as a result of some court action sparked by the notice from the Comptroller’s Office or was quashed after the letter was mailed. Nonetheless 137 letters were mailed to people with felony charges, resulting in 99 arrests, or a 72 percent clearance rate. As it pertained to those wanted on misdemeanor charges, 1,224 notices were sent by mail and 703 arrests (57 percent clearance rate) were made.

Benefits

When I testified before the House and Senate committees, one of my pressing selling points was how this law would have a direct impact on deputy/officer safety. We all know under normal conditions deputies/officers seek out wanted individuals at their homes, at an accomplice’s home, at their place of employment or during a traffic stop. At any of those locations, the law enforcement officer’s safety is at risk. At any of those locations the arresting officer must be concerned with weapons being used against him, the possibility of a subject resisting arrest, and/or flight. We all know in this business sometimes the direst things happen during the service of misdemeanor warrants. The mindset behind this law would cause the arrestee to come in to a sheriff’s office or police station and turn themselves in while being less confrontational.

This law also provides a wanted person a number of options which do not exist under normal circumstances. First, an arrestee can select the time and place where he/she is arrested. Secondly, it gives the arrestee time to retain an attorney, get bail money together, take off of work or arrange for child care if necessary. Without this law, someone arrested is simply not afforded these conveniences.

When the first applicable tax season pertaining to this law came into effect, the stakeholders were anxious to see how effective the new law would be. As it turned out, it proved to be extremely efficient and effective. The bait got a lot of action, clearing both misdemeanors and felony warrants, some of which were very surprising. Instead of your staff spending countless hours on the computer investigating the whereabouts of wanted people, or driving from location to location in hopes of finding someone, this law brings them to you.

Going forward

Anyone who has attempted to have a bill passed before their legislature knows the labor of love that goes into achieving this type of goal. No matter the glaring benefits of officer safety, cost, efficiency, effectiveness and conveniences for all involved, there were always elected officials who would turn the idea into something negative. For three years the Warrant/Tax Refund Intercept law produced remarkable results. I was happy to see after a successful first year, and much tireless testimony and support by the Maryland Sheriff’s Association and Maryland Chiefs of Police Association, the law was amended to a five year pilot just in Anne Arundel County.

After much lobbying by members of the House, Senate, Maryland Sheriff’s Association and Maryland Chiefs of Police Association, the law finally got approval in 2016 as legislation giving individual counties the option to opt in or out of the provisions set forth. Therefore, in 2017 those counties that opt in will be experiencing their first outcomes of the Warrant/Tax Refund Intercept law.

About the author: Ron Bateman is the Sheriff for Anne Arundel County Sheriff’s Department. If you have any questions or want more information about our Warrant/Tax Refund Intercept law please email him at [email protected].