When I ask you - what time is it? Just tell me the time, do not tell me how to make a clock. Does this sound familiar? There seems to be an apprehension with some leaders to complete all of the research and perform due diligence before responding to a decision. This quest for research can sometimes become inhibiting in making good field decisions. We have stressed out an entire generation of field commanders with analysis paralysis. ‘Give me all of the facts’ will require more time than you can afford under evolving circumstances. When you perform a windshield size-up of an event, this is often quick, a down & dirty size-up before getting out. There is a mindset of tactical decision making.

The first twenty minutes into an event often writes the script for the rest of the movie. This may become an action thriller but we need to avoid horror movies. Preconceived decision making is often done before arrival, but experience will tell you that no two calls are the same. Granted we all have had similar but never, ever the same. However, you use the historicals as a foundation. Your decision to manage the incident via past experiences still needs the perception of others for this event. We manage events, we may try to control them but the goal is not to let the event control you. What are the values of all the people’s perceptions? Each call will have different officers involved. Their experience and competencies will adjust their perceptions to this situation. Listen to your staff and trust is a true commodity! While speaking about your staff – how do you train them. If you train them by the text book only, you will shortchange them. Teach also with past experiences, both positive and negatives. Past victories are great teaching points. My personal experience is cluttered with valuable failures, or ‘learning moments’; share these teachable moments as well.

The tempo or the pace of an event will vary and create adjustments to your timeline - time is always a major factor. The hardest thing to do is to reverse an incident once you have begun. Once you perceive that you have screwed up, the reversal and readjusting (unscrewing) portion is often the flashpoint.

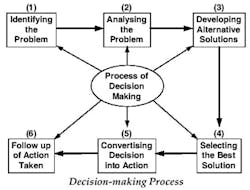

The tendency to over-focus on one focal point creates an inability for the brain to scan all the answers. There are many areas we glean information from to form a strategy, most are intertwined. The questions and focusing on other issues may seem to slow you down. However, slow can be fast - you look at everything and do not have to back up for missed points. You want to analyze the problem first. When we ask why it happened or what could happen, we may miss the full problem. Investigations start at the onset, but fully understanding the problem first is foremost. Do not forget the basic command questions of what we know (knowns), what we do not know (unknowns) and what do we need to know (facts). Granted, rapidly evolving fluid events are subject to many variables. Do not forget environmental or weather factors, they always throw a curve ball to you. Law enforcement applauds and requires rapid decision making. The part here is refining the strategy forming process to create good outcomes.

Many times, we forget to assess all of the hazards. Some may be unknown at the time. Here is the problem, your ability to adjust to new issues is the real test. I recall working on a hurricane evacuation of a city and county. One of the main traffic evacuation routes was backlogged. The day prior there was an multifloored building adjacent to the route that was ravaged by a tragic fire. The structure was about to collapse, for safety the entire motorway was blocked. Bottom line – life safety for the past incident verses another life safety evolving incident. Tough decisions and fast analysis was required. The building was dropped rapidly, counterflow traffic stopped and opened up one lane outbound until debris cleared. It all worked out.

Evaluate potential consequences is a simple statement, and nobody has that size of a crystal ball. Your experience, your staff’s experience and everyone’s insights will all add up here. Granted, we will all miss a few. The goal here is to minimize our mistakes. Everyone recalls their first few ‘big calls’, it is not that we freeze up on the possibility of failure but we move too judiciously instead of a safe pace. Once you get there and get some optics on the matter, the process moves forward. Your evaluation will be based on your knowledge, skills and abilities coupled with the core competencies of your staff. You cannot use luck as a plan, it helps but not the full plan.

Now, you and your staff determine appropriate response actions. The plans should be based on facts, discipline, and the circumstances of the incident. Often times we forget the choke points, not in traffic; but the choke points of the entire process to a good decision making. What is going to be the flashpoint? Sometimes we forget the important issues and over realize the emerging issues. It is all basic command 101 with a response design to guide you.

William L. Harvey | Chief

William L. "Bill" Harvey is a U.S. Army Military Police Corps veteran. He has a BA in criminology from St. Leo University and is a graduate of the Southern Police Institute of the University of Louisville (103rd AOC). Harvey served for over 23 years with the Savannah (GA) Police Department in field operations, investigations and completed his career as the director of training. Served as the chief of police of the Lebanon City Police Dept (PA) for over seven years and then ten years as Chief of Police for the Ephrata Police Dept (PA). In retirement he continues to publish for professional periodicals and train.