Police Facility Design Roadmap: 9 Steps to Building Your Most Effective Station

As an architect, I have visited many police stations during my career as a design professional. I have walked through many stations guided by dedicated law enforcement professionals who work tirelessly in deficient office spaces. While I’m there, I listen intently to sworn and civilian personnel describe the work they do each day as I tour the building and learn as much as I can about their daily duties asking them to imagine what a new, more efficient workspace, office, break room, or locker room should be like for them. When I know the answers to all these questions, I know what is operationally necessary for the project and how to plan a new or renovate the existing station. This is how a public safety architect identifies and builds the foundation of your station – by intimately understanding how you work.

Operations-based design is a roadmap to strategically designing a law enforcement facility that is a safe and secure work environment for sworn and civilian personnel. That way, your department is welcoming to the community that it serves as well as it's employees. Sounds pretty simple, right?

Step 1: Form your strike team

A modern law enforcement department is a highly complex and technical facility. Gone are the days of the simple station house. With the intensive operational space needs for personnel, equipment, and security, building a new police station or remodeling an old facility can be a daunting assignment. How do you navigate the different functions of patrol, investigations, records, booking, dispatch, an evidence warehouse, and more? How do you manage the technical and building code requirements of a mission-critical facility? What is resiliency and how do you address equipment redundancy? The answers to these essential questions are more easily uncovered by a “strike team” who will work together to understand the ins and outs of the project and to make informed decisions that serve the whole department.

In architectural vernacular, we call this strike team a facilities design committee. The members of the committee should be comprised of sworn and civilian representatives from each division and unit that will be housed in the station. It's best to keep the number of core committee members small, selecting participants who will provide support for the project. The committee may include city stakeholders, maintenance, public works, and elected officials when needed to gain their input on the project.

Step 2. Select your project advocate: Choose an architect

First and foremost, the facilities design committee should play a primary role in the selection of the architect and their team of engineers for the process. The architect will be your most trusted advisor and will work intimately with the facilities design committee to establish the size, schedule, and cost of the project.

Step 3. Build a strong foundation: Project goals and priorities

The committee will be tasked with establishing the overall goals and priorities of the project.

- Will this be a new or renovated station?

- What is the project program, budget and schedule?

- What are the resiliency, redundancy, and life safety targets?

- What are the strategies for hardening and security?

- What are the objectives for community and public uses?

To begin forming answers to these questions, your architect will prepare needs assessments, operational based programming, and feasibility studies for the committee to review and approve. For renovation projects, a building condition assessment for the building envelope and building systems will be needed.

Armed with information, the committee will arrive at a realistic project scope, schedule, and budget for the facility. Knowing the answers to these questions is the first step to a successful project.

Step 4. Define your facility: Drill down on operations

Your day-to-day tasks will define the composition and design of the facility. Understanding the operational needs, work adjacencies, challenges, and solutions of all the workspaces in each unit is important.

- Daily Operations — Thinking through the daily functions for all divisions and units is a large and critical task. Walking through your daily routine will help define the size and shape of each space and what amenities are needed to support the work. Imagine how you use each space and what would make the tour more efficient from the time you arrive at work, everything you do before briefing and afterward throughout your shift.

- Special Operations — Identifying the special operations anticipated for the project is another important task. This may include a war room for special teams, an off-site facility for undercover teams, an armory and tactical space for your SWAT team and vehicles.

- Volunteers, Community Policing, and Explorer Programs — Many communities have a variety of programs that support the police department; however, the people connected to these programs may not be law enforcement personnel and will not have the same access and security rights. Give thought to how to provide welcoming space in which these programs will thrive and support the department without compromising security.

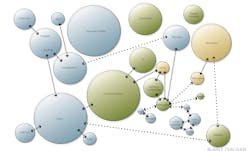

- Operational Adjacencies — This component takes a close look at which divisions and/or units must be located in close proximity to one another for maximum operational effectiveness. For instance, is it important for holding to be close to the sally port? Does patrol have daily or periodic interaction with traffic? Your architect can help you create an adjacency diagram that will visually show how all these divisions, units, and personnel work together daily.

- Workspace Requirements — Understanding the workspace requirements of each position within a division and unit will help ensure the operational needs are met in the final design. This is an excellent opportunity to establish standardized office and work station sizes as well.

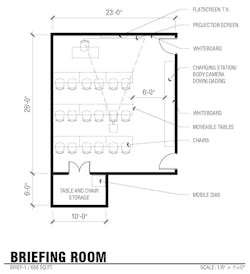

- Specialized Equipment and Furnishings — Select spaces within the station that will have very specialized equipment, which can have a large impact on the space requirements. As an example, where are body cameras charged and how is the information downloaded? Does this occur in the briefing room, watch commander’s office, or locker room? Understanding where specialized equipment is housed, when is it used, and by how many personnel at the same time can dramatically change the size and organization of a single room.

- Holding Facilities — It is important to determine what type of holding facilities your new or renovated station will include. While the building code and regulatory requirements for these spaces vary in each state, they are all highly specialized spaces. Understanding how your department will hold and/or transport suspects is essential.

- Access Control and Security — Using key cards and biometrics for access control is common in police stations. The department can limit and control access for all personnel from a computer and at a moment’s notice. Many times, the access control system for the entire city is run by the police department. Selecting a system that works well and is expandable is an essential decision to make in the planning stages of the project. Including cameras at strategic locations throughout the facility is necessary as well.

- Resiliency and Redundancy of Mission Critical Systems — How well your station functions after a natural disaster such as an earthquake, flood, tornado, hurricane, etc. is vital to establish early in the project. Resiliency is tied to the strength of select building components and systems and can be increased by building beyond the code requirements. This can be achieved by increasing the strength and load-bearing capacity of the building’s structural system to better withstand earthquakes or by enhancing the strength of the window systems if you are in an area where tornados or hurricanes occur. Redundancy is achieved by adding a back-up unit to the primary unit. The emergency power system is a good component to consider for redundancy design. If your emergency generator fails to fire up when needed, how will you provide power for your station in an emergency? Your answer may be to provide a secondary generator as part of the project to provide redundancy to the emergency power system.

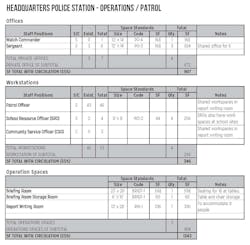

Step 5. Design organization: The program

An architectural program is a report that brings all of the operational information together and organizes it in categories following your department’s organizational chart. The program documents the personnel, equipment, and space needs of your facility. Your architect will create a program document that summarizes all the desired components of the project within each division/unit by position, space type, space size, and timeline.

Step 6. Develop the design: What does it look like?

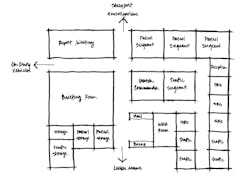

Once the program is complete, your architect will begin preparing plans that depict the entire facility. Architectural plans graphically illustrate the design of the building(s) and site. The architect will prepare a basic conceptual building space adjacency plan, which will incorporate the major space groupings identified by the program to demonstrate adjacencies and priorities consistent with the program. This conceptual plan will help the facility design committee to validate the minimal building area required for the new or renovated facility.

A site plan will be developed at the same time as the building space adjacency plan to “test-the-fit” of the building on the site:

- How might the new facility fit within site constraints and easement on the property?

- How will the existing facility expand to accommodate the growth needed?

- What are the key access points for the public and personnel?

- Is there enough space for public parking, secured personnel parking, and secured departmental vehicle parking?

- Is there space for construction staging and lay down?

Once the initial round of drawings is reviewed and approved by the committee, the architect will develop the site plan and building floor plan(s). The floor plans show all the spaces knitted together representing all of the program and operational requirements for the number of spaces, adjacencies, circulation, doors, windows, furnishings, and equipment. Building exterior elevations may be developed at this same time to show each side of the building along with a roof plan.

As the committee reviews the building floor plans, they should bear in mind the program requirements and test if the design meets the:

- Daily and special operations

- Volunteers, community policing, explorer programs

- Operational adjacencies

- Workspace requirements

- Specialized equipment and furnishings

- Holding facilities

- Access control and security

- Resiliency and redundant mission-critical system requirements

Step 7. Define a budget: The money

Based on the project program, site plan, and building floor plan(s), the architect will develop a conceptual project budget for the committee to review. The project budget includes an opinion on hard construction costs based on similar-sized police station facilities in your state. The soft costs will include construction market escalations as well as assumptions for professional fees, furnishings, equipment, permits, special inspections, moving costs, contingencies, and other owner costs for the project. Adjustments to the project budget should be discussed with the project program in mind.

Step 8. Establish a schedule: Can I have it tomorrow?

Developing a comprehensive project schedule will aid the Facilities Design Committee throughout the project. The schedule should identify major milestones and durations for each phase. These milestones should include assumptions for predesign work such as needs assessment, programming effort, and initial studies. The schedule should include typical durations for schematic design, design development, construction documents, and review periods for the committee at each phase of work. Assumptions for permitting and the duration for construction should be included to complete the schedule.

Step 9. A quality project: Are we there yet?

Designing any public safety project is demanding and challenging work yet is an enriching experience. Take it from someone who has shepherded many police departments through the design and construction process, it takes years of dedicated work by the entire design and construction team to achieve an effective quality project, and gaining a firm understanding of your operational needs is the critical first step to establishing a strong foundation for planning and building your most effective station.

Candice Wong is a Principal and head of the Public Safety team at TEN OVER STUDIO, headquartered in San Luis Obispo, CA and with offices in San Jose, CA and Bend, OR. She has dedicated over 20 years of her career to strategically planning, designing, and implementing public safety projects.

About the Author

Candice Wong, LEED AP BD+C, CQM

LEED AP BD+C, CQM

Candice Wong is a Principal and head of the Public Safety team at TEN OVER STUDIO, headquartered in San Luis Obispo, CA and with offices in San Jose, CA and Bend, OR. She has dedicated over 20 years of her career to strategically planning, designing, and implementing public safety projects.