Understanding Vision Enhancement Devices

It was almost 20 years ago that a chief of police received a request from his training officer to attend a low light operations course. The chief was understandably surprised because, after all, it’s using a flashlight right? You turn it on and you turn it off. How complicated can the training be? The chief hesitantly relented and the training officer spent a week attending the low-light course. It was eye-opening for both of them. Even taking into consideration the amount that was learned about light, strategies of use, decision making, and more, it was just the tip of the iceberg where operations in low-light conditions are concerned. There are plenty of other tools that can either augment, or replace the use of, the flashlight. This article will take a look at three technologies that do one or the other.

All of them specifically empower “seeing” in low-light conditions but at least one of them also can serve other purposes in bright light conditions as well. Let’s take a look.

As we discuss technologies that help us see in the dark, it’s first important to understand that very few circumstances are truly dark. What most of us refer to as “dark” is really something between dusk and star light. True darkness—a total lack of light—is hard to find (ask any insomniac who depends on it to get a good night’s sleep). That said, since we humans need data to make decisions and roughly 80% of that data comes to us visually, the less light there is the less data we receive and the harder our decisions are to make. When you are walking into an unknown risk potential conflict situation that’s a bad thing. You need all the light—or visual data input—you can get. Enter the technologies that help us “see in the dark.”

The three technologies we’re going to examine are night vision, thermal technology, and infrared technology. They all function differently and provide a different view when used.

Night Vision

Put simply, night vision goggles take what little light is available and amplifies it through a series of electronic filters and magnifiers to display a more easily viewed image on a screen. It’s important to understand that while you can get telescopes and binoculars that incorporate night vision technology, the light is not passing through the system from one lens to another. Typical magnifying devices, like the mentioned telescopes or binoculars, take light in the collective end (objective lens), magnify it and display it through the eyepiece (viewing lens). In those systems, light passes through nothing but lenses, magnified along the way.

In a night vision system, light still enters through an objective lens at the collective end, but that light is then manipulated electronically to be displayed on a screen through the viewing lens or eyepiece. Effectively (and very simplified), the light coming in is converted into electrons that are multiplied and then projected onto a screen that the user can view. Through the multiplication and magnification of the electrons, what the viewer sees is brighter than what is coming in through the objective lens.

There are usually only two challenges. First, they can be cumbersome and bulky. As technology develops and is miniaturized, this isn’t the challenge it used to be, but night vision equipment is still, in general, larger than thermal or infrared equipment. Second, because what’s seen is (essentially) multiplied electrons instead of actual light, the screen viewed isn’t color correct and is usually a mix of white, green and shades in between.

Thermal

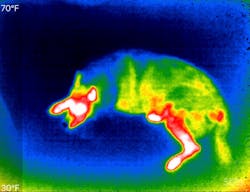

While many (if not most) night vision devices allow you to see with less light available, thermal viewing equipment doesn’t show you light at all. Instead, thermal viewing equipment shows you heat signatures or, more specifically, objects with differing levels of heat being projected from them. As an example, if you were using the night vision devices as described in the section above “in the dark,” you’d see all of the objects within your viewing area in the same color pallet and with no regard for how warm or cold they might be. In other words, a rock could be as clearly viewed and seen as the suspect standing next to it or trying to hide behind it.

Thermal viewing differs in that it reveals different levels of heat coming from any object. If you’re searching for a suspect hiding in the bushes at night, night vision equipment may not help at all, but thermal vision would clearly show the suspect’s body heat behind the colder and more diffused plant heat. Other examples would be looking at two vehicles side by side: if one is glowing red and the other is black, then the red one was recently running—it’s showing the heat. The brakes would likely show the same differences.

Infrared (IR)

Interestingly, the heat energy being “seen” by thermal cameras or viewing equipment is actually infrared (IR) energy. The difference between thermal viewing equipment and IR viewing equipment is most often simply in how it is displayed. Most thermal “cameras” (really heat sensors converting heat to patterns for viewing) show as a variety of colors depending on the heat levels. Black is most often the colder end of the spectrum with yellow being warm and red being hot. A lot of IR “cameras” (really the same thing as thermal cameras: heat sensors that convert heat to viewable patterns) use black for the colder end of the spectrum with white as the hottest end.

One of the strengths of both thermal and IR is that the actual temperature of the object or people being viewed doesn’t really matter. What matters is the difference between it and the surrounding environment. The system will sense and display the temperature variations and it’s the difference displayed that creates the shapes we recognize. That’s the intent, at least.

In testing a thermal camera, our team went out after dark and used the system to view various animals that could be found. One German Shepherd dog didn’t appear to really be shaped like a dog. As he sat and watched us walk by, we viewed him and the shape we saw wasn’t readily recognizable as a dog. It looked more like a big bowling pin that had a red core, some yellow outlines and then was surrounded by black. The bowling pin shape was the body of the dog but the head was barely red, leaning more toward yellow (orangeish?) and then surrounded by the black of the rest of the yard. It’s worth noting that none of the trees, out-buildings or shrubs showed up in the thermal camera.

This reminded us of a case wherein a couple detectives went to a house looking for a suspect. The family readily let the detectives in and said that no one else was in the house. The two people that were home said they had been watching television for most of the afternoon. They were seated on a sofa in front of the television. Off to one side there was a recliner. One of the detectives had a small thermal viewing attachment for his cellphone and when he fired it up, it showed that the recliner was “hot” as compared to the rest of the room. Someone had been sitting in it. Was it possible that it had been one of the other two people? Yes, but it would have made no sense. The detective was able to use that tidbit of information (that someone had been sitting in the recliner) to get the other residents to admit the suspect had just been there but went out the back door when he heard the detectives pull up. He was later caught nearby. The point is that thermal and IR imaging devices can be used for surveillance and investigations as well as direct operations—where night vision provides a better image to operate from.

Lt. Frank Borelli (ret), Editorial Director | Editorial Director

Lt. Frank Borelli is the Editorial Director for the Officer Media Group. Frank brings 20+ years of writing and editing experience in addition to 40 years of law enforcement operations, administration and training experience to the team.

Frank has had numerous books published which are available on Amazon.com, BarnesAndNoble.com, and other major retail outlets.

If you have any comments or questions, you can contact him via email at [email protected].