The importance of upper body strength to a police officer is unquestionable. To effect the arrest of a non-compliant or combative suspect requires that you have enough strength to secure his arms for handcuffing.

If handcuffing suspects was the only task we ever had to perform, having tremendous upper body strength might be sufficient. But, when you consider the possibility of having to deliver an effective strike with a baton or personal body weapon, evade an attack, shoot while moving, or quickly move to a position of cover, the importance of stance, footwork, and lower body mechanics is evident.

Stance

Stance is so hotly debated, particularly as it relates to shooting, that an entire book could be devoted to this topic alone. There are "die-hard" proponents of both the "Weaver" and the "Isosceles" methodologies. While it is not my intent to compare and contrast these shooting techniques, I intend to provide a glimpse as to the advantages and disadvantages of each strictly from the perspective of stance, footwork, and lower body mechanics.

Weaver

The Weaver method involves the shooter standing in a bladed position, with his shooting side to the rear. This position makes you less of a target, whether in a shooting or fighting situation, and helps to protect your centerline targets (eyes, throat, solar plexus, groin, etc.). Another benefit of this bladed position is that it keeps your gun further away from a subject than if you were facing the subject squarely. For these reasons, officers typically use this type of stance when contacting subjects (often referred to as the "position of interview").

As you can see, the Weaver stance has its strengths. However, critics of this stance are quick to point out that our body armor is designed to offer more protection from the front than from the side. This stance tends to expose the "Achilles heel" of our body armor, which is the area under the armpit, above the armor. Rounds impacting this unprotected area have resulted in the death of countless officers.

Many officers consider this stance to be awkward or unnatural. Proponents of the Isosceles stance (described below) claim that in a shooting or other highly stressful incident in close quarters, the officer's instinctive response will be to square his body to the threat, regardless of the officer's prior training. Another drawback to the Weaver stance is that it limits your field of fire, while hindering your ability to move quickly in any direction.

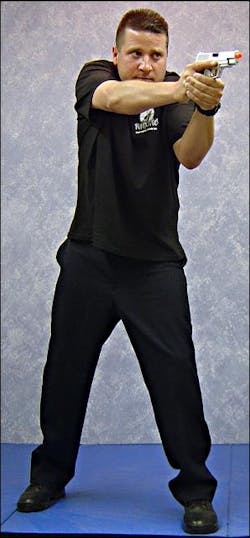

Isosceles

The Isosceles stance involves standing squarely to face the threat, with your feet approximately shoulder width apart. Many officers prefer to place their dominant side foot back slightly. This is arguably a more natural response to a spontaneous type of assault. From this squared position, you can easily move in any direction. You can also achieve 180-degree coverage without stepping, by rotating at the waist like the turret of a tank. This stance also places the bulk of your body armor between you and the threat.

The Isosceles is not suited for contacting subjects, because your centerline is exposed. Also, since your feet are positioned along the same line, you could very easily be pushed backward and lose your balance. Additionally, this stance does little to protect your holstered firearm.

Remember that the epitome of a good stance is one that provides both mobility and stability.

Footwork

In the case of footwork, think "small steps" when shooting and "big steps" when fighting.

Small steps enable you to move smoothly while minimizing head and muzzle bounce. This translates to a more stable shooting platform and more accurate rounds on target.

Moving forward

When moving forward with a "heel to toe" step, with your knees bent and your body leaning forward slightly, in an aggressive posture, you should feel your weight distributed on the balls of your feet. This allows you to pivot quickly in any direction.

Moving rearward

When moving to the rear, it's a good idea to glance over your shoulder to note any obstacles between you and your destination. A quick glance should enable you to make a mental note of the curb that's two steps to your right, the broken bottle directly behind you and the rear bumper of the Hummer H2 in the parking lot. Your "mind's eye" will help you negotiate from point A to point B without having to constantly look behind you.

Even though you're moving to the rear, your weight should be forward, on the balls of your feet. As you move, drag the ball of your foot on the ground, with each step. This will ensure that your heel is up (if your mind's eye lied to you and you collide with the curb, you want your heel up to "feel" the curb prior to committing your full body weight into the step). If your heel is down, the curb will probably hit you back after you fall!

Footwork for fighting

When fighting, large lunging steps enable you to quickly evade an attack or explode into the suspect with a powerful technique. Striking with the rear hand from a bladed stance will enable you to generate tremendous power. When moving forward, lunge with the lead leg and allow the rear leg to catch up. Reverse the order when moving to the rear.

Moving laterally

Whether shooting or fighting, lateral movement is generally accomplished by stepping first with the foot that corresponds to the direction of movement. This is essential to avoid crossing or entangling your legs and literally tripping over your own feet. Also, should you take a round or even a punch while your legs are crossed, you're likely to be knocked down like a bowling pin.

Lower body mechanics

Believe it or not, your legs were designed for more than getting you close enough to punch a suspect. Your legs are an integral component of generating powerful and effective strikes, whether using a baton or personal body weapons.

For illustrative purposes, let's consider the body mechanics involved in the execution of a proper palm heel strike.

From a bladed stance, with your left leg forward, push off the ground with your right foot to begin accelerating toward the suspect. Next, rotate your hips counterclockwise to incorporate the power of your entire body. Now, rotate your shoulders counterclockwise and thrust your right palm under the suspect's chin. KABLAM!

In this case, the whole is far greater than the sum of all the parts. Timing is a critical factor and can only be developed through repetition.

Train hard and stay safe!