How to Catch A Criminal: Catch, Escape, Repeat (Part 1)

Every officer with a decent amount of time on the job knows the unexpected turns an investigation can take. Seeing a major case through to completion often involves giving up on a theory and taking your investigation in a different direction as new information becomes available. In How to Catch A Criminal, we look at the many ways not-so-perfect crimes are solved. This month, how an escaped fugitive, guilty of murder and accused of several other federal crimes, is walking free.

This article appeared in the September/October issue of OFFICER Magazine. Click Here to subscribe to OFFICER Magazine.

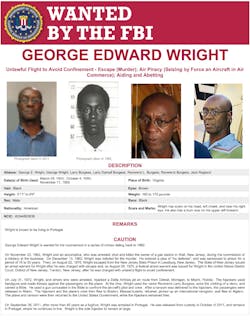

When you are criminally charged under a municipal ordinance, perhaps for a speeding or littering violation, the penalties are most likely minor. A small fine or perhaps a week in jail if you are a repeat offender. If you happen to commit a more serious offense, or that same minor offense in an area where municipal ordinances do not apply, you will probably face state level charges. Misdemeanors and initial appearances for felonies are handled at the Magistrate level, with penalties as serious as a full year in jail, as well as larger fines and probationary terms. Above that is the district court, which handles felony cases which can carry sentences as severe as years or even life in prison depending on the type of crime committed. If you should happen to violate a federal law, or commit a crime which crosses state lines, those cases are naturally handled in the federal courts. As expected, punishments for federal crimes are even more harsh than those imposed at the district court level. These court levels create a logical pattern: lower court and lesser crimes means smaller punishment, and higher court with major crime means severe punishment. It stands to reason that once a criminal offense has gone across state lines, and even beyond national borders, that an international crime must carry the most severe penalties of all. Oddly, taking your crime spree international can muddy the waters enough that you might be able to escape punishment altogether.On Sept. 26, 2011, Portuguese authorities arrested 68-year-old Jose Luis Jorge dos Santos. Mr. dos Santos was brought to a nearby police station where he was questioned about his whereabouts prior to living in Portugal. After some discussion with investigators, he was provided a copy of his arrest warrant and informed his arrest was part of an operation conducted by an FBI, U.S. Marshals joint task force. The name on the arrest warrant however, was not Jose Luis Jorge dos Santos.

On Black Friday, 1962, four people, three men and one woman, with pantyhose obscuring their faces, made off with $200 after an armed robbery at a motel in Englishtown, New Jersey. Evidently, $200 wasn’t enough to comfortably split four ways, and they decided to attempt another score. They headed to Wall, New Jersey, where the robbers, two of whom were armed with guns, entered a gas station. There, they demanded money from the owner of the store, WWII veteran Walter Patterson. At some point during the hold up, one of the robbers shot Patterson before they fled the store with an additional $70. Patterson succumbed to his injuries two days later. That same day, 19-year-old George Wright, Walter McGhee, Elizabeth Roswell and Julio DeLeon were arrested, all charged for their part in the robberies and the murder. It was determined the fatal round came from McGhee’s gun, but in the eyes of the law, all four assailants played a part in the murder. Walter McGhee was sentenced to life in prison in February of 1963.

In order to avoid a trial with the possibility of a death sentence, George Wright plead no contest to his charges. Wright’s sentence was 15 to 30 years in a New Jersey state prison. Four years into his sentence, George Wright was transferred to Leesburg State Prison, a prison farm which was a maximum security facility.

Leesburg relied on watchful guards and regular inmate counts to ensure there were no breaches of the perimeter, which at the time was not fenced. After a few years there, George conspired with George Brown, a man he befriended in prison, and two other inmates to escape. On August 19, 1970, after the 10 p.m. hourly count, the four men slipped passed guards, hot wired the warden’s car, and set out for Atlantic City before the 11 p.m. count began. In Atlantic City, the two Georges caught a bus to New York before settling in Detroit. The other two escapees were soon recaptured.

Now in his late 20s, Wright was quickly tiring of life on the run. He and George Brown shared a home with Melvin McNair, a U.S. Army deserter, and his wife Jean. Wright also had a girlfriend at the time, Joyce Brown, who supported his “on the lam” lifestyle. All three men were wanted, broke, and low on options. They wanted a fresh start without the law on their trail, so after two years in hiding, the group planned their next escape. George Wright, George Brown, Joyce Brown and the McNairs along with Joyce’s daughter and the McNair’s two children booked seats on a flight from Detroit to Miami on July 31, 1972 under false names. They procured firearms and disguises, which would allow them to blend in until they made their move. Two hours into the flight, Reverend Larry Darnell Burgess, formerly known as George Wright, dressed in traditional holy man attire, stood up and drew a handgun from a cutout in the pages of the Bible he was carrying

For the conclusion of the story of George Wright, visit officer.com/53071608

About the Author

Brendan Rodela is a Deputy for the Lincoln County (NM) Sheriff’s Office. He holds a degree in Criminal Justice and is a certified instructor with specialized training in Domestic Violence and Interactions with Persons with Mental Impairments.

About the Author

Officer Brendan Rodela, Contributing Editor

Sgt.

Brendan Rodela is a Sergeant for the Lincoln County (NM) Sheriff's Office. He holds a degree in Criminal Justice and is a certified instructor with specialized training in Domestic Violence and Interactions with Persons with Mental Impairments.