How to Catch A Criminal: Picking Up the Pieces

Every officer with a decent amount of time on the job knows the unexpected turns an investigation can take. Seeing a major case through to completion often involves giving up on a theory and taking your investigation in a different direction as new information becomes available. In How to Catch A Criminal, we look at the many ways not-so-perfect crimes are solved. This month, a terrible crime and the survivor who carried on, hoping for justice.

The natural reaction to experiencing tragedy or loss is grief. That tremendous feeling of sorrow caused by the death of a loved on can be overwhelming. It can cause sufferers to fall into severe depression, which itself can be debilitating. Survivors of tragedies which result in the death of some victims may face an additional hurdle. The phenomenon known as Survivor's Guilt can manifest in those who were lucky enough to make it out of a traumatic event alive, when others did not. These thoughts of “why me, why not them?” are often a symptom of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Most people can hardly imagine the emotional burden of losing the most important person in their life in a violent event, and carrying on without them, weighed down by the idea that it should have been them in the victim's place. Trying to move on from this sort of devastation would surely feel impossible. In law enforcement we often encounter people who are suffering to varying degrees. It is paramount that we do our best to help these people as best we can, even if solving their case won't help their suffering.

On January 9, 1972, Jackson Schley and his wife Daisy arrived home to their apartment in Seattle's Central District. Upon walking through their front door, The couple were confronted by an armed man. The unknown male ordered the Schleys to the floor at gunpoint. With the frightened couple lying face down, the intruder fired his gun twice. As his wife knelt beside him, Jackson Schley took his final breaths. As an added insult, Jackson's wallet was pulled from his pocket by his killer. Daisy was then forced out the backdoor of the apartment and into the man's car. He drove her away from her home, a few miles away, where he ordered her to undress. Daisy was raped before being kicked out of the vehicle and told to walk away from the car. As she complied, she was bludgeoned over the head and fell to the ground, unconscious. Her husband's killer fired his gun again, striking Daisy in the head, before he fled the area. What the killer failed to realize was he had only grazed Daisy's head. When she came to, Daisy Schley began screaming for help and her cries were heard be a nearby resident who found her and called 911.

Police arrived and learned the events of the night from Daisy. The crime scene at the apartment was processed and DNA was swabbed from Daisy's undergarments. This DNA sadly did not produce a match in any available database. Despite the thorough investigation and DNA evidence, the offender would go unnamed for 37 years. The DNA sample however was eventually entered into the state's collective DNA database, just in case a match was ever found. Daisy Schley was forced to carry on from that night, knowing she had watched her husband die, and she narrowly escaped death herself. Daisy Schley carried the weight of this tragedy with her for 35 years, until she passed away in 2007. Almost certainly, Daisy Schley wondered at times why she was the survivor, rather than her husband.

Though Daisy died before her husband's murder could be solved, she did live long enough to see the legislation passed which would eventually bring her attacker to justice. In 1990, the state of Washington passed RCW 9A.44.130, which required people convicted of a sex offense to register with their county sheriff's office, whether or not they are a permanent resident, or only in the state temporarily for work or education. In 1999, RCW 43.43.754 was passed, which required everyone registered under RCW 9A.44.130 to also provide a DNA sample for potential criminal investigation and identification purposes. These laws opened the door for many cold cases to be solved, as the state's DNA database would be flooded with known standards from convicted felons who may have gotten away with other crimes in which DNA was present. Many states now have similar laws in place, and tons of unsolved cases from around the United States are finally being closed.

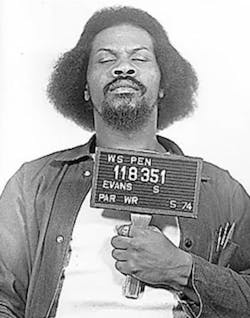

In 2009, a convicted sex offender, recently released from prison in Nevada, moved to Washington. As required by Washington state law, he provided a DNA sample when registering as a sex offender. It turns out, this was not his first time in Washington. The man was 74-year-old Samuel Evans. Evans had spent nearly 40 of the last 50 years of his life behind bars for a myriad of crimes, including armed robbery and sexual assault. After returning to Washington, he would add manslaughter to the list, albeit more than 3 decades after the fact. Once his DNA was entered, it eventually came back with a match to the DNA found in Daisy Schley's underwear after she was raped. Additional testing also revealed Evan's DNA was also present at the scene of another unsolved murder in a Seattle neighborhood in 1968. In that case, 43-year-old James Keuler was found stabbed to death in his apartment. There were no signs of forced entry, but bloody footprints and a broken knife at the scene indicated there had been a violent altercation with someone else in the apartment. DNA taken from cigarette butts were matched to Samuel Evans once he registered as a sex offender.

In 2010 Samuel Evans was formally charged and arrested, once again finding himself behind bars. In 2011, Evans insisted he was merely the fall guy in the Keuler murder, and wasn't the killer, though he was present at the apartment. Evans also completely denied involvement in the murder of Jackson Schley. Despite these denials, Evans did eventually plead guilty to both counts of manslaughter, with the caveat that he did not commit the crimes, but the evidence would compel a jury to find him guilty anyway. A judge sentenced Samuel Evans to 20 years in prison, which may sound lenient, but at 74-years-old and in poor health, this was essentially a death sentence. These sex offender and felon DNA laws allowed detectives to solve two dormant cases decades after the fact. These sort of reforms in the criminal justice system are a welcome contrast to the not-so-tough on crime policies we've seen sweep the nation in recent years.

About the Author

Officer Brendan Rodela, Contributing Editor

Brendan Rodela is a Sergeant for the Lincoln County (NM) Sheriff's Office. He holds a degree in Criminal Justice and is a certified instructor with specialized training in Domestic Violence and Interactions with Persons with Mental Impairments.