Bring Your Crime Scene to Life

It is tempting to consider a homicide investigation complete when the handcuffs go on the suspected perpetrator. In reality, this is just the beginning. Of far greater consequence is identifying and establishing the facts of the case; in other words, what is the truth of the matter? Investigators must avail themselves of all the tools at their disposal for identifying and interpreting the facts so they may arrive, to the best of their ability, at the truth. Convictions. Justice. Accountability. All of these are subservient to the truth; truth is built upon fact; fact is supported by evidence.

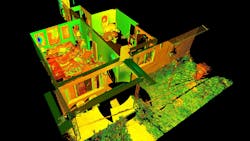

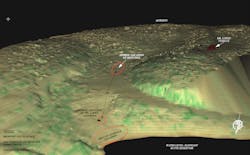

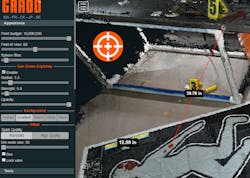

A tool that is becoming much more commonplace in the quest to document and preserve evidence in its context is the 3D scanner. In the rapidly evolving world of technology, “3D scanner” may be too narrow of a term. Names such as Leica, FARO, Z & F and Riegl are commonplace in the laser scanning community. Matterport and L-Tron provide specialized camera systems for 3D capture; companies like GRADD (Global Robotic and Drone Deployment) train investigators to use ground and aerial-based cameras to produce 3D models and point clouds. A variety of software suites like Pix4D and Reality Capture may be used to convert photographs into stunning 3D views. Speed, accuracy and visualization are the name of the game. Amid all the clamor and excitement of new and improved technology, however, it behooves the investigator to take a moment and asked the question, “Of what value and for what purpose is the data being collected?” In other words, how does 3D scanning help the investigator document evidence, interpret fact and discover truth?

Documentation of evidence

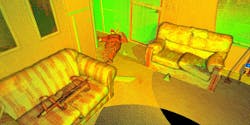

Much of crime scene work is identifying, documenting and collecting evidence. Evidence is not always a physical object or property that may be documented and collected. The absence of something can be powerful evidence. When documenting evidence (or the lack thereof), the investigator should ensure the process is thorough and complete. Photography is standard practice and an indispensable aspect of an investigation. In major investigations, such as homicides, it is also important to consider spatial relationships.

Sometimes, long after a scene is released, new information is learned which would have changed the way an investigator initially documented the scene. In an effort to adequately and reasonably document a scene, some details may not have been documented which later prove important to the case. A 3D scanner is an objective collector of data. It makes no decisions as to what should be collected or disregarded. It has limitations, to be sure, but decision and discernment are not among them. On normal, full-capture settings, a scanner will collect all data within its field-of-view, density and distance parameters. Though the operator may elect to limit some aspects of data capture, the documentation process is much more objective than manual measurements. It is not uncommon for 3D scanners to collect data on scene which proves useful at a later date.

Not only do these systems provide objective and balanced data capture, they are becoming ever more portable. Laser scanners, once essentially restricted to cumbersome elements attached to large tripods, are becoming smaller and faster. Investigators can opt to use the more robust scanners; smaller, more portable scanners or even handheld, mobile units.

Interpretation of evidence

After the data has been collected, next comes the task of interpretation. Endless streams of data do little to inform the investigator of what actually happened. Evidence, like puzzle pieces, must fit together to form a clear picture. Many of the pieces of this proverbial puzzle have be irrecoverably lost. This means the investigator must deal with a very real fact: not everything may be known. Evidence may be destroyed, lost or incomplete. Regardless, it is the task of the investigator to strive to understand evidence in its context. Context. A small word occupying a crucial place within an investigation. Only something observed and interpreted in its context is of use to the investigator. Without context, evidence is vastly malleable. Context, however, provides rules and parameters, an anchor to reality and understanding.

Discovering the truth

The goal of any investigator should be finding the truth. Investigations are not opportunities to grind a particular axe or arbitrate comeuppance. Investigators are neither judge nor jury, rather they are to be objective purveyors of evidence, fact and truth. A mindful investigator relies on the facts to point him/her to what actually happened. 3D data allows the investigator to virtually return to a scene at his/her discretion and leisure without the hassle of obtaining new warrants or dealing with an altered scene.

The ability to view the scene from varying viewpoints corresponding to witness statements, victim accounts and suspect testimony gives the investigator an opportunity to compare the evidence with the different (or differing) statements. Could a witness have seen what transpired from their vantage point? How was the victim oriented when the crime was committed? Could the suspect have interacted with the scene in ways that contradict or support his/her account? 3D data provides many opportunities for such comparison.

How do the various elements and methods of 3D capture help in major investigations? Much in every way. Distilled to three main thoughts, the capture of 3D data allows for the documentation of evidence, the interpretation of fact and, ultimately, the discovery of truth. These elements can combine into powerful demonstratives providing the Tryer of Fact a clear picture of what may or may not have happened. 3D capture is here to stay and may be predicted to become more commonplace. How will it benefit your investigations?

Agent Clint Norris has been with the New Mexico State Police (NMSP) for 12 years. He has been part of the NMSP Crime Scene Team for 7 years and has assisted 24 counties with crime scene processing. Norris has extensive knowledge and training in multiple forensic disciplines and including attending and completing the National Forensic Academy. Norris is also part of the Crime Scene Investigation Subcommittee for the Organization of Scientific Area Committee for Forensic Science in Crime Scene Investigation.

Agent Clint Norris, New Mexico State Police

Agent Clint Norris has been with the New Mexico State Police (NMSP) for 12 years. He has been part of the NMSP Crime Scene Team for 7 years and has assisted 24 counties with crime scene processing.

Norris has extensive knowledge and training in multiple forensic disciplines and including attending and completing the National Forensic Academy. Norris is also part of the Crime Scene Investigation Subcommittee for the Organization of Scientific Area Committee for Forensic Science in Crime Scene Investigation.