"Katie's favorite word was ‘zest.' She loved the sound of it, loved what it meant. And Katie lived her life with zest. She used to say, ‘Wake up every day expecting something wonderful to happen.' She looked forward to each new day," her parents Dave and Jayann Sepich write at www.dnasaves.org, the site of a non-profit association they formed to help educate policy makers and the public about the value of forensic DNA.

Katie's life was cut short in 2003 when the 22-year-old graduate student at New Mexico State University was brutally raped, strangled to death, set on fire and abandoned at a dumpsite near her home. Although no strong suspects emerged, skin and blood under her fingernails produced a full DNA profile, which was uploaded to the FBI's Combined DNA Index System (CODIS).

"When Katie was raped and murdered, I thought the guy who did this to her was obviously such a horrible person that he would get arrested for something else, they would take his DNA and we'd have him," says Jayann.

She soon learned it was illegal in New Mexico to collect DNA upon arrest and that DNA samples were only uploaded to state and federal databases upon felony conviction.

"I was stunned," she recalls. "I just assumed when someone was arrested they took their fingerprints, their mugshot and their DNA."

Three long years later the Sepichs received some closure in their personal tragedy when the New Mexico DNA database matched the unknown DNA profile collected at the scene of their daughter's murder to Gabriel Avila, who by then had been convicted for several other crimes. But if New Mexico had required a DNA sample for Avila's felony arrest in November of 2003, Jayann says investigators might have solved Katie's murder sooner and caught this murderer before he roamed free for three more years.

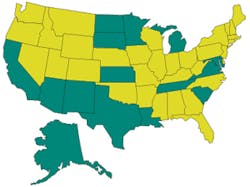

The Sepichs championed the cause of collecting DNA upon arrest in New Mexico, and in January 2006, the New Mexico state legislature passed "Katie's Law." This legislation requires law enforcement to collect DNA for most felony arrests and upload it to the state DNA databank. The state of New Mexico became the sixth state to enact such legislation, and to date there are 15 states with similar laws.

Arrestee legislation makes senseArrestee DNA legislation just make sense, stresses Jayann. Research shows that often perpetrators of stranger murders are or will become serial killers. A recent city of Chicago study seems to support this. The Chicago examination followed the criminal histories of eight convicted felons and found that had officials collected DNA upon their first felony arrests, they would have prevented 60 violent crimes, including 30 rapes and 22 murders.

The criminal history of Chester Dewayne Turner further bolsters the case for arrestee DNA. Police arrested Turner for assault with a firearm on January 26, 1987, but released him due to lack of evidence. Law enforcement arrested Turner 21 more times before he received a conviction that resulted in DNA being taken and uploaded into the state of California DNA databank, where his profile matched DNA evidence found on 12 rape and murder victims. Turner committed his first murder in March 1987, less than two months after his first arrest, so had his DNA been collected it is possible a11 of his victims would still be alive, Jayann reports.

She contends the new law is working as intended in New Mexico, where there have been 49 matches since January 1, 2007. "It's really incredible the way it works," she says. "Forensic DNA doesn't just work in theory, it works in practice."

Civil rights violation?Laura Neuman's story bears striking resemblance to that of Katie Sepich in that DNA is what finally landed her attacker in prison.

Neuman was raped when she was 18 years old, and it took police nearly 20 years to identify her attacker, though he'd been arrested at least six times before her attack and six times afterward. Alphonso Hill pleaded guilty in 2002 to raping Neuman and was sent to prison for 15 years. A DNA sample taken in prison led to charges in six other rapes, and police say Alphonso is a suspect in at least 20 additional rapes in the Baltimore, Maryland, area.

Neuman maintains he could have been stopped far earlier, if DNA had been collected sooner.

She went public with her story and began lobbying for a law that would require police to take DNA samples from everyone arrested for a violent crime. And in January, Maryland legislators signed a bill into law that expands its DNA database by collecting samples upon arrest for certain felonies.

To supporters, building a DNA database with samples from the unconvicted is no different than collecting fingerprints, but critics say it's a violation of civil rights and that it opens the door for a person's genetic "fingerprint" to get into the wrong hands.

Not so, says Dr. Tod Burke, a criminal justice professor at Radford (Virginia) University, who has coauthored several publications relating to the examination of national and international DNA databases. He says the DNA collected for identification is classified as junk DNA, and does not contain genetic data. In fact, forensic technicians only examine 13 to 15 loci out of 3 million markers when using DNA for identification purposes. If someone studies the resulting profile, they cannot learn whether an individual has diabetes or is susceptible to certain types of cancers or diseases, Burke states.

That being said, he warns rules and regulations must be enacted to ensure DNA data is not misused in any way. "You assume the people you hire are professional and will not abuse their authority," he says. "But there needs to be specific guidelines and proper supervision to prevent misuse."

Associate Attorney General Kevin O'Connor tried to quell worries over the misuse of DNA in a recent press release, where he stated, "Congress has passed a provision that says anybody who abuses this information, or uses it for non-law enforcement purposes, such as to look at someone's family history of diabetes or whatever the disease may be … will be prosecuted."

But other precautions must be in place in addition to tough laws, states Sepich. Fortunately, much is already being done to protect this information. Every DNA profile is converted into a data string, so that anyone hacking into the system receives a series of numbers and little more. The information housed here also does not have a name or serial number attached to it, just a code. This code corresponds to identifying information housed in a separate database, which is not linked to the DNA database in any way. "If someone got into one database without accessing the other, they wouldn't even know whose profile it was," Jayann stresses. "There's been a tremendous amount of thought put into guarding these databases."

Tracking DNA expungementCivil libertarians warn that DNA samples taken from individuals arrested for certain crimes will likely remain in the system, even if the suspect is exonerated. However, federal law requires states mandating the collection of arrestee DNA to include a provision for expungement if the arrestee is found not guilty or never prosecuted.

How this is done varies from state to state. Some states have automatic expungement where a state department follows each and every case, then either expunges or retains the DNA. New Mexico officials decided a more cost-effective approach was to have arrestees file for expungement. In this state, arrestees simply write a letter asking the state to expunge their DNA, and it's done. "This saves a tremendous amount of money," Jayann says. "Automatic expungement would have cost the state approximately $100 a sample."

But Michael Smith, a professor from the University of Wisconsin – Madison, is not convinced. "How do we know if they have destroyed the sample?" he asks in an interview with CourtTV. "It's a problem that's not really resolved by saying we have a law against it."

To help assuage these fears, states not only must put safeguards in place limiting the use of DNA samples, but also need to publicly demonstrate they are in compliance, according to the issue brief, "Improving Public Safety by Expanding the Use of Forensic DNA," put out by the NGA Center for Best Practices in 2007. The document reports states may need to employ an oversight body or mandate audit trails tracking DNA use. The good news is that many states have already done this. For example, New York, Texas and Virginia established commissions responsible for monitoring DNA evidence handling.

While protecting individual privacy is an issue, Jayann maintains she, and many other law-abiding citizens, would not have a problem with their DNA being collected and put in a database for law enforcement use, stressing that the only time it becomes an issue is if a DNA profile matches DNA at a crime scene. "If you don't commit a crime, there's nothing to fear," she says.

When DNA evidence from a crime scene does match a profile in the database, it may be explained away in that the individual visited the home or site frequently. But if the profile came from under a victim's fingernails, for instance, that's harder to explain. But even if a sample matches a suspect, officials run another DNA test to ensure the individual's DNA matches the database profile a second time.

No price tag for safetySupporters maintain arrestee DNA collection makes the criminal justice system more efficient and effective, while naysayers say collecting DNA for every arrest costs more. But for victims like Neuman, or affected family members such as Jayann, you cannot put a cost on these measures. "If you have the possibility of keeping a serial rapist or murderer off the streets, what kind of price tag would you put on that?" Neuman asks.

Furthermore, the cost is not as high as one might think, especially when compared to the expenses incurred in unnecessary investigations and prosecutions. It costs the state of New Mexico $80 to collect, process, analyze and upload a sample. In comparison, Jayann says authorities spent more than $200,000 investigating her daughter's case before capturing her killer. Even the expense of keeping an offender incarcerated appears cheaper than leaving a violent felon on the streets. In fact in 2000, economist Philip Romero estimated incarcerating an offender can save up to $200,000 annually in victim and social costs.

According to Burke, collecting arrestee DNA is cost-effective over the long term. "What is the cost of a homicide? If you catch the person, you stop them from committing crimes and provide a victim's family some relief. How can you put a price on that?" asks the former Maryland police officer. "The question isn't can we afford to do this, the question is can we afford not to?"

Backlog concernsDNA databases are only as useful as the amount and quality of information they contain. The idea of collecting more profiles seems like a good one, but some people question how this will impact the current DNA backlog. The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) estimates the backlog of rape and homicide cases at approximately 350,000 nationwide. The NIJ also estimates there are 300,000 backlogged offender samples and more than 500,000 samples yet to be taken from offenders.

However, supporters say collecting DNA from arrestees can actually reduce DNA backlogs. In fact, Jayann reports New Mexico no longer has a DNA backlog since it began arrestee DNA collection. The state sends arrestee samples to a private lab, where they are processed when the lab has approximately 80 samples. And while there is a slight delay, Jayann says it is nothing compared to the delay she experienced with her daughter's case.

New Mexico's success can be duplicated, Jayann adds, by adequately funding the DNA arrestee program. The state of New Mexico put funds in the budget at the program's onset, and hired forensic technicians to expedite DNA collection and processing.

Putting arrestee DNA into the system may help solve cold cases and prevent future ones, thus saving states enough money to invest in the people and technology needed for additional DNA processing, Burke adds. Let's say a rape today costs more than $100,000 to society (a reasonable number given that a rape was estimated to cost about $87,000 in 2000). If an offender commits eight rapes and a DNA database catches the offender after rape four, the database match will have prevented four rapes, and saved society approximately $400,000.

"Although the initial costs of developing a DNA database may be high, the cost undoubtedly will decline over time," says Burke. "When compared to the estimated costs of crime, the initial costs can easily be justified."

Ronnie Wendt | Owner/Writer, In Good Company Communications

Ronnie Wendt is a freelance writer based in Waukesha, Wis. She has written about law enforcement and security since 1995.