Chicago PD Sorts, Tests Vast Number of Guns in Battling Violence

By Jeremy Gorner

Source Chicago Tribune

Each year, the Chicago Police Department’s firearms laboratory receives thousands of guns that police officers confiscate and take off the streets.

Handguns arrive at the lab’s intake desk in brown paper envelopes. Rifles get there in gun boxes. Ballistics evidence such as bullets and shell casings are sealed in plastic bags.

“Every day, we get guns dropped off, and it could be as few as 15 to 20 guns, and there’s days, on busy days, we get over 200 guns,” said Sgt. Norman Kwong, a supervisor in the firearms lab at the Homan Square Chicago police facility on the West Side.

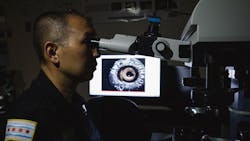

In a cramped office just past the intake area, firearm technicians sit at their desks with some of those guns in front of their computers, logging in their makes, models, serial numbers and other pertinent identifiers. Some officers examine casings and bullets under microscopes.

The technicians may thumb through the office’s robust reference collection of gun books — “Rifles of the World,” or “Antique Firearms,” among many others — if they’re unfamiliar with some of the more obscure weapons that come through the door.

Occasional loud bangs echo through the office.

It’s the sound of guns being test-fired to determine through a ballistics exam whether a weapon recovered on the street is connected to a particular crime. In instances where a gun was found by police at the scene of a shooting, the test-firing process would require a technician to shoot that weapon with department bullets before comparing shell casings under a comparison microscope to others that were collected at the crime scene.

There are two rooms used by the firearms lab for testing.

One is a small firing range for fully automatic weapons, as well as other more powerful firearms. They are fired by a technician into a black wall covered in a rubbery material. Shotguns are test-fired into a trap device, which captures their pellets.

The second room has a trough-like water tank where officers fire semi-automatic handguns — or guns that fire one bullet per trigger pull — through an opening, with the water slowing and then stopping the bullets. Those slugs are then retrieved from the bottom of the tank and the ejected shell casings are gathered from a so-called “brass catcher,” a piece of netting located behind the tank near where the guns are fired.

A technician then examines the casings under a microscope, looking at tiny markings that might match those left on casings recovered from a crime scene, not unlike a gun’s fingerprint of sorts, signaling that the same gun might have been used.

Some of these markings are from a gun’s firing pin, which is forced into the back of a casing when a gun is fired; markings that form when intense pressure is exerted in the gun’s chamber; and extractor markings left when a shell casing is ejected from the weapon. Findings are then peer-reviewed by a firearms examiner who also works in the CPD lab.

“Can there be human error? Absolutely. But for the most (part), there’s a lot of work that goes into (determining and verifying) that a fired cartridge is fired from a certain firearm,” said Kwong.

The technicians also submit a sample of shell casings, whether they’re from a test-fired gun or one from a crime scene, into a computer that uploads high-resolution images of the evidence into a database for the National Integrated Ballistic Information Center, or NIBIN, a program that has been around since the 1990s and is administered by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

Through ballistic imaging, NIBIN technology compares shell casings collected by law enforcement and scans them through its voluminous computerized system to see if they match casings from other shootings, based on their markings. Chicago police have been using NIBIN since 2013.

“There is a considerable body of peer-reviewed research that shows that every firearm imparts very unique tool marks on that (shell casing),” said William King, a criminal justice professor at Boise State University, who has researched law enforcement’s use of ballistics evidence. “And so, the firing pin, the breech face, the ejector and the extractor … they’re unique from one gun to the next gun.”

But this technology has limitations. Chicago police stress NIBIN’s links among shootings merely denote a “high confidence correlation,” or high probability, of matches — not 100% — and can only be used as leads for detectives to aid in their investigations, not as actual evidence.

And just because Chicago police learned through NIBIN that a gun could have potentially been used in multiple crimes doesn’t mean detectives are looking for one shooter. In Chicago street violence, guns get passed around constantly, bought and sold in the underground market, and even stolen from legitimate owners or gun dealers, often making it difficult for investigators to ultimately make an arrest.

If detectives want anything NIBIN-related to be used in court, confirmed ballistics matches can be made only by a certified firearms examiner from the Illinois State Police crime laboratory who analyzes the evidence by hand.

Even then, some research has questioned the underlying reliability of ballistics matches. For instance, a forensic science report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice in 2009 noted that even with computerized images to assist in their analyses, a finding from an examiner “remains a subjective decision based on unarticulated standards,” and the margin of error in such decisions is unclear.

King said he’s unaware of any studies showing high error rates for firearms identification. And the ATF has defended the reliability of NIBIN, saying that as of June of this year, internal reviews of the computer program’s preliminary ballistic matches show a 99.6% confirmation rate.

The Tribune sifted through hundreds of records to understand the impact that a single Glock 17 9mm handgun had on Chicago’s streets. After it was stolen from a gun shop in Superior, Wisconsin, on New Year’s Day 2016, NIBIN technology linked it to 27 shootings 460 miles away in Chicago, mostly on the West Side, from early February 2016 until it was taken off the street by police in late July 2017.

At the Tribune’s request, King, the expert from Boise State, looked at a report showing where those 27 shootings occurred. He wasn’t surprised to learn they occurred close to one another, many of them in North Lawndale and other nearby West Side neighborhoods. King said research on firearms ballistics often shows guns used repeatedly don’t travel very far.

Meanwhile, at the CPD firearms lab, hundreds of guns in envelopes were stacked on shelves in the water tank room. They were sitting in boxes waiting to be test-fired, said Kwong, the sergeant in the firearms lab.

“We’re about a month or two behind,” he said, “based on the sheer volume of guns.”

______

©2021 Chicago Tribune.

Visit chicagotribune.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.