Shoot/No Shoot Scenarios

Across the country, most of range training is on square ranges, shooting two-dimensional training targets. If your agency is fortunate enough to have a range with three-dimensional or moving targets, your agency has made a great investment. Most others have simple ranges. It is important to vary the training, and make it effective. One thing every agency needs to do: Incorporate critical decision making into the training.

Critical decision making can include several tasks for policing. On a simple level, the use of shoot/no shoot scenarios can be added to any training plan. The next level should be treating de-escalation as a perishable skill and adding it to regular range sessions.

OFFICER Magazine March 2022 Digital Edition

Mental health and use of force

Right now, we are living in a society that is trying to normalize mental health crisis and adult temper tantrums. The numbers suggest that 1 in 4 arrests involve a mental health issue and at least 12% of all people entering the mental health “system” are introduced to it by the police. It appears that this rate has increased over time.

Law enforcement officers are likely to encounter a person in mental health crisis on a daily basis. Unfortunately, these incidents tax resources that some agencies do not have. For example, most officers have to “sit” with the subject during evaluation and finding bed space, if the evaluation ever even gets to that point. This takes an officer out of commission for that time.

This is another problem with mental health cases. Officers don’t just see a subject once and the issue is resolved. They see mental health patients, often the same patients, over and over again. Sometimes the officer’s presence is instantly triggering, forcing the officer into split second decisions. Other times, the same person is docile, depending on their condition. In some cases, a mental health professional may even do an over-the-phone screening, sometimes by the officer having to hand that person his cell phone.

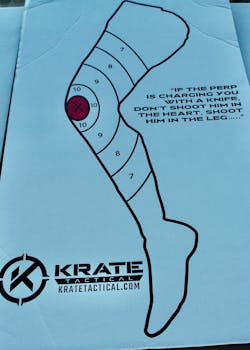

Even if the officer has done all they can do to negotiate and de-escalate in a given situation, they are often forced to exercise a lethal force option. This isn’t something we can readily communicate to the “Why don’t you shoot him in the leg?” public, but our training needs to include this fact also. Otherwise, officers exercising force options would never find closure on some incidents.Social perception and threat

In an experiment on social perception of threat, scientists showed computer generated faces to research subjects, and asked them to decide which faces appeared “threatening.” These faces were designed by the researchers, and ranged from “threatening” to “harmless.”

Subjects were shown fewer and fewer threatening faces over time. Subjects tended to expand their definition of threatening. The number of threats a subject had perceived depended on how many threats the subjects had seen lately. In another study, it was found that experienced officers make better decisions and shoot more accurately than rookies, given the same potentially lethal encounter.

The truth is, training in decision making, both threat and de-escalation, improves the overall response for law enforcement officers. The best thing an agency can do is to provide their officers with a wide variety of training scenarios, and integrate this training into an officer’s career survival plan.

Using simulators

One way for officers to be subjected to decision making is to use simulators. There are complete solutions that offer a variety of situations and training solutions. One complete solution is the MILO Training Solutions theater (faac.com/milo/solutions). They offer a number of options, including a 180-degree and even an almost 360-degree theater, giving officers full training immersion into a scenario. The training scenarios are incredibly realistic and they approach all kinds of situations. Since these solutions cover other municipal functions, like passenger bus training, fire, and EMS training, agencies can leverage their grant-based funding from different sources for a simulator.

Since humans form concepts inductively when it comes to scenarios, having officers of any training level train by scenario is valuable. Training inductively means that a person can form general principles or conclusions from a specific, or even detailed, experience. This is the guiding principle for placing a rookie on FTO, by the way.

For example, the general layout of a scenario cannot be duplicated, simply because of varying landscape, but the idea of the scenario is duplicated internally. While on FTO (centuries ago, by the way), I once was dispatched to a possible DV case on a second story of an apartment complex. The victim had reported that the suspect may harm himself. When I ended up talking to him, it was on the balcony. I positioned myself between him and a possible suicide route, which was the railing.

After the call, my FTO asked why I stood where I stood. I told him I wanted to prevent him from jumping, if he intended to jump. He asked me, “What if he intended to take you with him?” I carried that lesson throughout my career every time my call overlooked something that otherwise would be called scenic.Use a variety of targets

On a square range with paper targets, I use printed photos of hands holding cell phones and guns to provide a mix between “shoot” and “no shoot” targets. I cover these targets with stacked barrels or target stands, where the Officer has to walk up to the scenario. All scenarios require verbal commands. If you learned anything from Three Skills Every Officer Should Have (Officer.com/21233801), practicing effective verbal commands should be integrated into shooting and negotiating.

Your range can be improved using the same stuff IDPA clubs use: Walls made of 2” x 4” frames with snow fencing stretched across them. These create safe barriers, because they allow anyone to be able to see if someone is down range. Two walls attached at 90 degrees are self-supporting, and they don’t blow over in the wind.

I use three basic targets, pasted on a IPSC cardboard target: Gun, Phone, and Hands Up. Using the most basic setup, Officers can face away from a target until they are given the “threat” command, where they turn around and engage.

Your training is only as good as your AAR

Without some sort of dialogue following a training scenario, the training really doesn’t have any value. An After Action Review must begin with an open dialogue such as, “why did you do that in that manner, officer?” Everyone should be encouraged to participate in an AAR. This is where inductive learning is very important. During an AAR, sometimes the discussions can go off topic.

For example, during one AAR in which I participated, we were talking about making shooting decisions, and the topic of crime victims. The facilitator let everyone digress a little, and someone was talking about what happened after a shooting in a domestic violence case. They were saying that victims of personal crimes, including those related to DV cases, have just experienced a complete loss of control in their environment. If the officer wishes to establish any kind of relationship with the victim, they have to allow the victim to reestablish some control. I asked how they would do that. The facilitator told us that asking simple questions like, “May I sit down here?” allows that person to have a little control of their environment. I never imagined that I’d hear one of the most powerful pieces of investigative advice in a firearms class. If the AAR flows from topic to topic, let it, within reason. Have particular training goals, and take opportunities to lead your training group toward these goals.

Have a multi-echelon approach to training

Multi-echelon training is an approach where training participants participate in their aspect of training, or in their capacity, as part of a larger training mission. Agency critical response teams participate in multi-echelon training all the time. For example, during a training session, the hostage negotiation team may be working on their equipment or negotiation skills, while be precision shooters are practicing wind doping.

The training doesn’t necessarily have to be limited to a single agency. For example, in a municipal organization, city fire can be working on training updates for an engine, the police department can be working on pre-positioning rescue assets, while other officers can be doing qualification. The training goal for a multi-echelon project could be something like responding to a mass casualty incident.Two final rules

All training should be task oriented, not time oriented. Down time determines the length of time for non-structured events. When it comes to training, there is one rule that every coach knows: Never walk away from a failure. When a basketball coach has their team practicing foul shots, the final shot always has to be a score. This way, no player walks away from a failure. It is the same for shooting training. Every training session, regardless how problematic, must end in a pass. This doesn’t mean that everybody passes automatically. This means that every training session is task oriented, not time oriented. The task is completed until it is completed correctly.

Without documentation, the training never happened. That is, every training session needs to be documented. The document must be organized in a manner that demonstrates that the particular goals of the training were completed. All police training is discoverable. The manner in which it is recorded should take this into consideration.

Having said this, because it’s about the level of detail in training documentation. The particular tasks of the training need to be outlined. While it is reasonable to score every qualification, the final score is based on pass/fail. This is a lesson learned for some agencies whose exceptional or dismal marksman have had to use the firearms in the course of their duty. When it comes to liability, all training needs to be simply pass/fail.

Every Agency can, and should, train regularly. The training should be varied, and goal oriented.

About the Author

Officer Lindsey Bertomen (ret.), Contributing Editor

Lindsey Bertomen is a retired police officer and retired military small arms trainer. He teaches criminal justice at Hartnell College in Salinas, California, where serves as a POST administrator and firearms instructor. He also teaches civilian firearms classes, enjoys fly fishing, martial arts, and mountain biking. His articles have appeared in print and online for over two decades.