What if, when an officer was on duty, central dispatch and command personnel always knew where they were, when there were moving faster, and when they stopped moving?

What if, when an officer was on duty, central dispatch and command personnel knew when they had unholstered their sidearm, if it was leveled and aimed at a suspect, and if it was fired?

What if, when an officer was on duty, central dispatch and command personnel had access to their physical health and could tell when their heart rate sped up, blood oxygen dropped, temperature spiked or if they were wounded?

These questions are no longer what ifs. Today’s wearables can do more than track a wearer’s steps or record the calories consumed. As the above examples illustrate, they can monitor all kinds of things. Wearable technology has done this for consumers for years, but now it is available for on-duty officers. Only here, wearable use maintains more than just the wearer’s health; for law enforcement officers the data from wearables can keep them alive.

“ …the technology that everyday consumers are accustomed to using is now available for first responders to use as they engage with communities, prevent and resolve crises, look to communicate better, and stay safe. ”

— Reg Jones, Public Safety Lead, Samsung

Wearable technology is available for holsters and guns, body armor, smartwatches and uniforms. Though its use isn’t widespread yet, Reg Jones, public safety lead for Samsung, which offers its Samsung Galaxy Watch for officers, reports “this is an exciting time for public safety…because the technology that everyday consumers are accustomed to using is now available for first responders to use as they engage with communities, prevent and resolve crises, look to communicate better, and stay safe.”

Smartwatches for safety

Today’s officers increasingly use smartphones to carry out their duties outside the patrol car. The case for their use is obvious; a smartphone can be a hands-free device that can replace many technologies once carried on officers’ overloaded duty belts. Officers can use them to take notes, record conversations with witnesses, photograph evidence, and to communicate with each other and dispatch.

“The smartphone is becoming the central hub for first responder communication,” states Jones. “But the smartwatch is where we are headed. The smartwatch has all the capabilities of a smartphone and is an independent communications device.”

This wearable tool connects directly to the wearer’s cellphone carrier and does not require tethering to a smartphone. “This means officers can wear their smartwatch and leave their smartphone at home. The watch has a direct connection and a direct phone number,” Jones says.

Like a smartphone, a smartwatch, such as Samsung’s Galaxy Watch for first responders, has sensor technology built into it. Among these sensors is a gyroscope, GPS, an accelerometer, barometric pressure reader, heart rate monitor and an ambient light sensor. “All of these sensors have a unique purpose that can help a first responder,” adds Jones.

The gyroscope, for instance, can let dispatch and command know if an officer falls rapidly. Jones says to imagine a scenario where an officer must hit the deck quickly. In this case, the gyroscope lets police headquarters know that the device (and officer wearing it) have moved rapidly up or down. “This is powerful information if the officer is alone,” he says. “It prompts dispatch to begin inquiring about the wearer.”

A GPS sensor takes this further and enables dispatch to locate the watch and wearer in real time. GPS also provides the officer wearing the watch with his or her location in real time. “With GPS, dispatch or anyone in central command can locate first responders across a map and determine if they are where they are supposed to be, how long it will take them to respond to an incident, and to direct them to that incident,” he says. “When combined with the gyroscope, if an officer has fallen and doesn’t get up, dispatch also knows where to send paramedics.”

While the gyroscope gives hints on the direction of an officer, up or down; the accelerometer sensor hints on speed. “When an officer falls, the accelerometer can tell dispatch if it was a rapid fall versus a slow descent,” Jones says. He provides an example of a school resource officer. That officer might move 2 miles per hour (mph) on average, but if he suddenly starts moving 7 mph, the sensor detects the rapid change in speed and alerts dispatch. “This change means something. It means there was a change in conditions on the ground,” he says.

A barometer indicates the weather, but it’s also a pressure sensor. So, while GPS informs of an officer’s latitude and longitude coordinates, this sensor informs of his or her altitude. “If you’re in a dense urban area, the altitude can be used to determine if an officer is on the first floor of an apartment building or the fifth,” Jones says. “This information is critical if an officer is down. We may know the officer is in the northwest corner of a building, but if we also know he’s on the third floor, that is critical life-saving information.”

The heart rate sensor regularly checks the wearer’s heart rate. It can tell if an officer is relaxed, fatigued, or active. And, if an officer is shot on duty, the heart rate monitor becomes a source of vital information for dispatch. “As someone loses blood, it becomes harder and harder for them to communicate,” Jones says. “Having this heart rate monitor on the wrist of a fallen officer is quite powerful.”

Finally, smartwatches offer an ambient light sensor that automatically increases the watch’s brightness when an officer is outside in the sun, so he can still see the screen. Likewise, in a darkened alley, or while working undercover, that same sensor can dim the smartwatch so an officer can avoid detection.

“The ability to understand what officers are doing in the field can influence training, influence use-of-force relative to public opinion, and impact litigation if someone reports an officer after an incident.”

— Jim Schaff, vice president marketing, Yardarm Technologies

Samsung has partnered with five computer-aided dispatch providers to enable an extension of their CAD systems onto the Galaxy smartwatch so agencies can utilize available sensor technology to their advantage. In 2017, the Chicago Police Department began trialing the smartwatches with customized applications for officers on bike patrol.

The department equipped 10 Chicago PD officers with Samsung smartwatches equipped with Northrop Grumman CommandPoint Mobility, which allows CAD system interaction. With this capability, dispatch can alert officers about a call and send a green, yellow or red alert to warn them of its severity level. The watch utilizes haptic vibration technology to alert officers via vibration when calls come in. Officers interact with the watch to acknowledge these notifications, change their response or availability status, and to activate an emergency alert that notifies surrounding officers if they are in distress.

The trial has been a success, with Chief Jonathan H. Lewin, Chicago PD Bureau of Technical Services, reporting “It’s something we are looking to expand.”

Samsung’s Galaxy smartwatches use Samsung KNOX, a defense-grade mobile security platform designed to keep hackers at bay. “This technology ensures there is a high level of data encryption for all communications,” Jones says.

Wearables for weapons

“Our Gun Aware sensor, available for Glock Gen4 Models G17, G22, G34 and G35 handguns, has more capabilities. It can do full multi-axis, three-dimensional telemetry of the weapon, meaning it can detect if that weapon has been fired, and if it is in motion throughout a use-of-force event. It can tell you exactly what an officer has been doing with the weapon, how he was holding it, if it was at rest at his side, if it was leveled and potentially aimed at a suspect. And if it is fired, it can tell you exactly when the officer fired it, how many times he fired and the direction he fired,” Schaff reports.

This information can be communicated via secure AES-encrypted Bluetooth Smart wireless technology to dispatch or central command to alert them of real-time events, or it can be leveraged locally, in the case of the holster sensor, to turn on body-worn cameras every time an officer unholsters his weapon.

This technology, which enhances officers’ safety in the field, also helps departments gain a better understanding of weapon use-of-force and unholstering. “If an officer makes a traffic stop, do they draw their weapon as they approach the vehicle? What do they do with that weapon throughout the call?” asks Schaff. “The ability to understand what officers are doing in the field can influence training, influence use-of-force relative to public opinion, and impact litigation if someone reports an officer after

Automatic injury detection

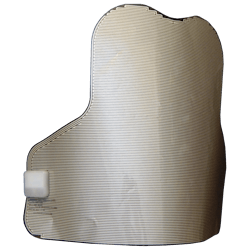

The Automatic Injury Detection (AID) system is comprised of sensors inserted into body armor. When this sensing panel in the body armor is pierced by a bullet, knife or shrapnel, the AID system sends an automated emergency alert to a phone, radio or via another communications system. This automated and instant emergency alert can help save lives, reports the AID website, by improving the ability and speed in getting medical attention and/or backup to affected officers.

The AID panel consists of a thin film with an encased conductive ink trace that covers the area of the film. When that conductive trace is broken by a sharp edge or bullet, AID detects the event and automatically sends an emergency alert over Bluetooth (or other communication method) to a phone or radio that can forward the notification through the communications infrastructure to emergency services, backup personnel, and/or dispatch/command. The panel is worn in the front and back—typically in the body armor carrier, in front of the ballistic panel. Each panel has two separate zones, enabling the system to detect injuries to the upper front, lower front, upper back or lower back.

The Rio Grande City (Texas) Police Department is among the early adopters of this technology. “This vest —if the officer were to get shot or stabbed, tells us which officer it is, the location, along with other components and sends a message to all officers with a department-issued phone,” Rio Grande Police Chief Noe Castillo told 4ValleyCentral in a media broadcast.

The alert even shows the exact GPS coordinates of the officer, his blood type and the weapon he is carrying.

“This is a faster response, [and it goes out] automatically,” Castillo told the media. “Officers won’t have to call it in—and seconds count when someone gets shot or gets hurt. Any added security and safety that we can give our guys working on the streets is always a plus.”

New world of tech

Every technology advancement also has a downside, and the wearable technology market is no exception. Here, officers are not always keen on their department tracking them and having personal information about them, and agencies are not always onboard with collecting volumes of data that the Freedom of Information Act might require them to share with the public. Both entities will need to evolve in their stance before the technology’s use becomes commonplace.

Jones predicts officers’ fears will lesson as the everyday acceptance of wearable technology grows. “The younger generation of officers is already accustomed to using this technology in their lives. They are accustomed to sharing data about themselves automatically through their devices,” he says. “And they’re demanding technology. As these officers are promoted through the ranks, they will want more and more mobile tech to be used every day.”

Schaff predicts the same for agencies as more cities mandate use-of-force reporting. “Chicago is one city that requires full use-of-force reports, not just in officer-involved shootings, from the police department,” he says. However, for now, he says, agencies are ever cognizant of the fact that every piece of data they collect on their wearable devices is subject to the Freedom of Information Act. This means, agencies often collect the data for real-time use, he says, but they do not keep it in a database to use for training, officer education or other purposes.

Even so, Schaff sees a day where these sentiments will change. “It is becoming a world where you cannot separate the officers from the department relative to the Freedom of Information Act,” Schaff concludes. “Officers may have their right to privacy but they are on duty working for a public safety organization, and the things they do are part of their work. Though there is currently a chasm between the two, technology will win as mandates and legal requirements persist.”

Ronnie Wendt | Owner/Writer, In Good Company Communications

Ronnie Wendt is a freelance writer based in Waukesha, Wis. She has written about law enforcement and security since 1995.