Stadium evac gets a new game plan

After the collapse of the stage at the Indiana State Fair that killed five people August 10 officials tried to determine if there was any way the tragedy could have been avoided.

The Indiana incident was the third outdoor show this summer where severe weather became the star by destroying a stage, placing band members and ticket holders in danger. During Cheap Trick's Ottawa Bluesfest performance July 17, rogue winds blew the roof onto the stage, jeopardizing the band and hundreds in the crowd. Then, on August 7, 80-mile-per-hour winds in Tulsa, Oklahoma, blew Flaming Lips' 15-foot video screen off the back of the stage.

Clearly, outdoor event managers could use a better weather warning apparatus. Receiving and acting on timely weather warnings, of course, is just one part of the problem. The other part is moving people quickly to safety after warnings are received.

Whole new ball game

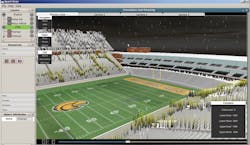

A new breed of crowd evacuation simulation software, called SportEvac, developed at the National Center for Spectator Sports Safety & Security (NCS4) at the University of Southern Mississippi was launched this summer. NCS4 was established in 2006 to provide an academic vehicle to improve security and crowd management protocols at the nation's major sports and music venues.

Annually, an estimated 200 million people attend sporting events at some 3,000 stadiums, arenas, and ballparks in this country. Million more buy tickets to concerts. The Department of Homeland Security considers any assembly of 350 or more people to be soft targets for terrorism. SportEvac was developed through a grant from DHS to give stadium authorities better emergency planning visibility.

Using blueprints from actual sports facilities, the Southern Miss researchers have created virtual, 3D e-stadiums that can be populated with as many as 70,000 individually animated human avatars programmed to respond to situational threats in as many unpredictable ways as humans might. With SportEvac, emergency managers can now see how fans behave, or misbehave, when spooked by natural or man-made security threats. Earlier evacuation simulators were generally limited to crowds of less than 10,000, which might work for smaller, indoor arenas but are not adequate when simulating crowd control at packed outdoor stadiums.

"Since it's nearly impossible to use a live audience for evacuation training, SportEvac provides us the capability of simulating a stadium or arena crowd virtually," said NCS4 director Louis Marciani.

Marciani said the key is planning and rehearsing. "I don't think you can get people safely out of a stadium without practicing because we don't know how crowds would react to things like a suicide bomber," he said. "Chaos will occur, but there can be organized chaos."

Recurring nightmare

Getting 12,000 state fair concert-goers or over 100,000 college football fans to safety in a hurry in the event of severe weather or some sort of terror attack or other emergency is a recurring nightmare for stadium security and disaster managers at any high-profile music or sports venue.

It's not just sudden bad weather in the form of high winds, lightning strikes, or tornados that worries stadium crowd-control officials. What keeps disaster planners, police, fire, hazmat, and other public safety officials awake some nights are visions of, say, terrorists launching several smoke canisters from a boat cruising down the Tennessee River just across Highway 158 into the south end zone of the University of Tennessee's Neyland Stadium during a Saturday afternoon football game. Or from a cart on the golf course that surrounds the Rose Bowl. Or over the wall of Wrigley Field from the sidewalk on Waveland Ave.

As the red or green smoke cloud drifts into the stadium the crowd will have no way of knowing the plume is harmless. The intent of the terrorists is not to kill anyone with the smoke. The intent, instead, is to incite a stampede for the exits among the fans.

The most common cause of stadium evacuation is severe weather. Other than the high winds during summer outdoor concerts, recent emergency situations related to severe weather or lightning have triggered evacuations of college football games at South Carolina, Virginia Tech, and Oklahoma universities. In April, Busch Stadium in St. Louis was evacuated during a Friday night baseball game when tornado warnings sounded and over 40,000 baseball fans were rapidly sheltered in place.

"Depending on location, most of our member stadiums utilize weather data reporting services or radar to anticipate a need for evacuation," said Mary Mycka, executive director of the Stadium Managers Association. Members of SMA have been on yellow alert since being identified as soft targets by DHS in 2001. The DHS Office of Infrastructure Protection encourages and funds means for stadiums to develop, test, and review evacuation plans. "DHS offers personalized and cost-free risk-assessment tools to our facilities," Mycka said.

It is after an evacuation order is given that concerns disaster planners. In nearly every weather-related evacuation, fans tend to panic and rush for the exists, clogging tunnels. The panic would likely be worse if thick smoke began drifting into the seats or an explosive device went off.

Since practice evacuations on a stadium scale are impractical, computer simulation systems have emerged to let disaster planners sleep better by giving them some insight into factors not easily tested in exercises.

Hence, the need for evacuation simulators like SportEvac.

Contact sport

SportEvac is meant to help stadium security and disaster planners answer key disaster questions tailored to specific scenarios, such as how can the facility be evacuated in the shortest time if IEDs are found simultaneously in, say, all the men's rooms, or how to shelter a capacity crowd in place due to drastic weather events, what the best ways are for emergency workers to get inside the stadium while frantic fans are trying to get out, or alternate ways to relieve inevitable parking lot gridlock.

There's more. Evacuating a stadium is a contact sport. Simulation wrinkles can be added. SportEvac is designed to simulate what happens in the event of unpredictable evacuation complications, such as the effect of wet concourse floors on fan movement or what might happen if the power goes out and exit corridors go dark. The system is also capable of assessing the impact on the evacuation of aisle-sitters too frightened to move, of wheelchair congestion in tunnel bottlenecks, of the harm that might be expected from inebriated bleacher bums, or of fans attempting to return to their seats to fetch field glasses, purses, or children left behind in the surge.

Not everyone attending a sporting event actually has a seat ticket. Many fans in some stadiums show up merely to tailgate in the parking lot and be part of game-day excitement. Currently, SportEvac has no facility to include the tailgating element in its simulations but eventually Marciani expects to include considerations for people outside the stadium in the package.

"If there's an approaching tornado, you're still responsible for those people who may be outside the stadium but still on your grounds," Marciani said. "How do you shelter them? Is there room to move them into the stadium? If so, how do you do that if you have a seven minute window?"

Marciani said eventual enhancements for SportEvac will be to include modeling routines that look at pedestrians, traffic patterns, and how nearby public transport fits in the picture. In the past two years, NCS4 officials have conducted over 60 Sport Event Risk Management workshops at collegiate and professional stadiums across the country. Marciani has begun to use SportEvac in the workshops. It's been beta tested at Roberts Stadium on campus, at the University of Tennessee, and at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Marciani says these workshops have resulted in the training and certification of more than 1,700 individuals representing 416 NCAA Division I, II and III institutions. The 2001 attacks inspired authorities at all collegiate and professional stadiums to a more heightened state of readiness in anticipation of what-if. In August, 2010, NCS4 hosted the inaugural National Sports Safety and Security Conference and Exhibition in New Orleans. More than 300 attendees and 43 vendors participated. The importance of stadium evacuation planning was signaled by high-profile keynote speakers DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano and NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell.

Squeeze play

During the on-campus SportEvac evacuation simulation at 35,000 seat Roberts Stadium, stadium management found it had to change its shelter-in-place procedures. "We learned during a sell-out that not everyone could be evacuated and sheltered-in-place on the concourses under the stadium seats as previously assumed during a severe weather event," Marciani said.

Marciani said typical tabletop exercise go like this. Stadium security says during lightning strikes or tornado warnings everyone will be moved under the seats to the concourses and that should do it. "Well, they've made an assumption but they really don't know if everyone will fit," he said.

When SportEvac modeled the evacuation, it was able to determine that only 32,000 of the 35,000 attendees could be safely evacuated to safety under the stadium. Now, stadium authorities must find shelter for the surplus in the nearby Student Union or some other safe structure.

"That's the beauty of SportEvac - it looks at your evacuation plans and forces you to make adjustments where necessary," Marciani said.

SportEvac's reputation is spreading beyond the halls of academia into mainstream professional venues. In March, a tabletop incident exercise was performed at New Meadowlands Stadium in New York City, home of the National Football League New York Jets and New York Giants. The purpose was to provide an opportunity to train stadium and security staff, local fire and police first responders, and emergency managers in what they might expect if an incident occurred during a major spectator event.

New Meadowlands management declined to characterize the results of the SportEvac drill. "This is confidential information," said director of Security director Daniel DeLorenzi.

Marciani said the overall goal of the New Meadowlands project was for stadium management and local emergency response teams to assess their preparedness and identify areas for improvement. "The exercise at New Meadowlands Stadium, and all future exercises, is important because the whole point is to prepare first responders - the better the training the more efficient the emergency response," he said.

Marciani expects to release a "lite" version of the system in August for no charge to all stadium and disaster managers. He anticipates a high demand for venue customization, which will likely require some sort of fee to accommodate the number of requests.

Other commercial evacuation simulation systems exist. One, from Regal Decision Systems, is appropriately called Evacuation Planning Tool, or EPT. EPT allows users to conduct evacuation analyses for stadiums or office buildings using a range of emergency situations and produces results that includes evacuation times, queue lengths, and chokepoint identification.

Another, called SimWalk, is an analysis tool that helps simulate and evaluate pedestrian traffic. Although designed more to understand airport and train station pedestrian flows, the University of Pennsylvania has used SimWalk to simulate evacuation of 18,000 people from Franklin Field during commencement ceremonies.

Douglas Page

Douglas Page writes about science, technology and medicine from Pine Mountain, Calif. He can be reached at [email protected].