Recently a Santa Cruz, Calif. police officer noticed a suspicious subject lurking around parked cars. When the officer attempted to make contact, the subject ran. The officer gave chase and when he caught the subject he learned he was a wanted parolee.

Officers later canvassed the area and found several unlocked vehicles but were unable to determine which--if any--the subject had gone into. But because there was an outstanding warrant for his arrest, the subject was taken to jail.

The arrest marks just another day in the life of a police officer out to predict and serve.

While officers have long taken an oath to protect and serve, the officer in the above scenario was patrolling the area in question using new technology that enabled him to predict crime hot spots and take action before a crime took place.

Though this case casts a public view on the technology’s ability to garner arrests, PredPol, named by Time Magazine as one of the Top 50 Inventions of 2011, is actually meant to reduce crime through increased police presence and deterrence, says Zach Friend, a crime analyst with the Santa Cruz PD.

While arrests occur because officers are in zones the software identified as crime hot spots, Friend explains the software’s true utility is in crime deterrance. “The officer [in the above scenario] went into a residential area he normally wouldn’t have been in and saw the individual coming out of a car that clearly didn’t belong to him and he made an arrest,” he says. “But how many people didn’t suffer their cars being broken into because of that officer’s presence?”

The statistics, he adds, speak for themselves. When Santa Cruz implemented the predictive policing software in 2011, the city of nearly 60,000 was on pace to hit a record number of burglaries. But by July burglaries were down 27 percent when compared with July 2010.

“We saw the same thing in the first six months of 2012 compared to 2011,” Friend adds. “PredPol helps hold reduces crime by increasing police presence.”

The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) is the largest police agency to embrace predictive policing, which crunches crime data in real-time to determine where to send officers. To date, the LAPD has implemented the technology in five divisions covering 130 square miles.

The valley’s Foothill Division, which was the first LAPD division to implement the technology, reports results that have turned even the most skeptical of skeptics into believers. “We saw a 12-percent reduction in targeted crimes during the six-month pilot. And we saw a 26 percent reduction in burglary alone,” says Capt. Sean Malinowski, who has worked with University of California – Los Angeles (UCLA) on the project since it was nothing but a gleam in a mathematician’s eye.

SUBHEAD: Crime factors

PredPol is the culmination of a seven-year study by a team of UCLA social sciences and mathematics researchers seeking to study factors that drive crime pattern formation. Anthropology professor Jeff Brantingham says researchers aimed to look into the factors that contribute to crime hot spots.

He explains, “Crime hot spots are very dynamic. In some areas, hot spots remain constant. But a lot of times hot spots come and go or spread or go on for awhile and then disappear.”

“But humans are not nearly as random as we think,” Brantingham continues. “Crime is a physical process, and if you can explain how offenders move and how they mix with victims, you can understand an incredible amount.”

Their research uncovered three key factors driving these apparent complexities:

n Repeat victimization. That is, if someone is victimized today, they’re likely to be victimized again in the future. Brantingham explains it’s like returning to a restaurant to eat there again after a positive dining experience the week before. “A burglar might say, ‘Wow, that was an easy mark, let’s go back there tomorrow.’ And then you see a cluster of crime,” he says.

n A crime next next door might put neighbors at risk for similar crimes. If the house next door is broken into, the neighbor’s house may be next because those living near each other generally share the same economic and social status.

n Offenders tend to commit crimes in their own backyards. When a house gets broken into, people often assume an offender from the “wrong side of town” committed the crime. “In reality, offenders search for victims locally, where they can fit in and avoid detection,” Brantingham says. “A person from the area knows the risks, knows environment, and fits into that environment. Someone from across town doesn’t know what the risks are.”

Knowing these factors contribute to crime patterns, researchers embarked on a study using LAPD crime data to learn whether or not software could predict crime. UCLA mathematician George Mohler began adapting mathematical algorithms, testing his computer models on several thousand burglaries that occurred in the San Fernando Valley during 2004 and 2005. He found success when he adapted an algorithm used to predict aftershocks following an earthquake.

“He started tweaking that algorithm because it matched up nicely with the theory of repeat victimization,” Malinowski says.

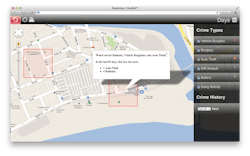

The resulting software, PredPol, helps police agencies solve the technical challenge of optimally allocating resources. An agency’s own records management system (RMS) pushes information on date, time, crime type and location to the software and the software crunches the numbers to determine daily crime hot spots. “They don’t have access to our RMS and the data is encrypted when it goes out,” Friend explains. “But though we encrypt the data, it’s public information.”

SUBHEAD: A force multiplier

Those currently using the tool call it a force multiplier; a boon for cash-strapped agencies that have seen manpower dwindle in recent times.

“Over the last decade, we’ve had a 20 percent decline in officers but a 30 percent increase in calls for service,” Friend emphasizes. Knowing that getting more officers wouldn’t be a reality for quite some time, the Santa Cruz PD instead focused its energies on unearthing technologies designed to better allocate its finite resources. The 94-officer department volunteered to test Mohler’s software operationally and helped craft a tool that officers would actually use.

“If a technology or tool makes the police officers’ job more complicated, they’re not going to use it,” Brantingham says. “What we were looking for with Santa Cruz was to deliver the information in such a way that it was easy to obtain and did not distract officers from other tasks.”

The Web-based tool provides crime prediction boxes as small as 500-feet by 500-feet to watch commanders in less than 30 seconds, says Friend. At both the LAPD and Santa Cruz PD, watch commanders log into the software, much like they would log into a Gmail account, to obtain the 15 hot spots for that shift. They then provide officers with a list of these locations and ask them to go into them periodically during their shifts.

Though both locales have made a conscious decision to focus their use of the software on burglaries, stolen vehicles and property crime, it’s also possible to select different types of crime. Santa Cruz PD’s specialty units utilize the tool to sort out predictions for specific crimes. For instance, the gang unit clicks on a box for gang-related crimes and obtains a distinct list of hot spots matching that criterion.

“We provide the information to the officers and leave it up to them to do something with it,” says Malinowski, who admits that at first he fielded plenty of questions from officers who wanted to know what they were supposed to do with the information.

“We told them to go into the boxes and use their knowledge, skills and experience to determine what should be done,” he says.

For instance, if a box indicates an area ripe for auto theft, a seasoned officer will drive into the area and immediately notice factors that put victims at risk. For instance, it may be a neighborhood with many parked cars along a dark street. That officer might then run license plates or speak with homeowners about the risk posed to their vehicles.

In an area identified as being at high risk for property crime, an officer might talk to people in a highly visible way. “They may stay there for just 15 minutes to a half-hour and let people see them walking around the area,” says Malinowski. “Would-be offenders see the police activity and are deterred from committing a crime there. All we are trying to do is deny them the opportunity to commit that crime in that time and place. During our test, we probably disrupted criminal activity eight to 10 times a week.”

Other officers go into these boxes at night and pull their squad car into a discreet location to watch who is out at 2 a.m. “They might notice a guy riding a bike around without a light on, and stop him for not having a light on his bike. They might find he has burglary tools on him, a stolen ID from a burglary that just occurred, and arrest might be made. There are different ways to approach this,” Malinowski says.

He believes the tool prevents crime by randomizing patrol. “Officers are told to go into the identified hot spots when they can, which automatically randomizes patrols in those areas,” he says. “The randomization deters crime because there is no longer any pattern to police patrols. Officers might pass through at 11:05 p.m. or 2 a.m.”

SUBHEAD: Intuition at your fingertips

But couldn’t a crime analyst or a seasoned police officer accomplish much the same thing?

Technically they could.

“This is no different--but more far more complex--than simply taking a good officer’s intuition and building upon it,” Friend admits. “An officer who has been around 25 years knows where crime is going to occur. When you’ve seen it enough, you know that certain times of year, certain times of day, certain events, and so on, will play into crime patterns.”

But PredPol puts this information into the hands of all police officers from the seasoned veteran to the rookie cop. “It’s like you’re giving brand-new officers all of that history and intuition,” he says.

It also expands the information a seasoned officer has at his disposal. A veteran officer might be able to list three, five or even 10 hot spots, but will struggle to come up with a list of 15, Friend points out.

“PredPol can do a perfect ranking of hot spots one to 20, and turn that information over to police to provide an optimal allocation of resources,” Brantingham says.

Still not convinced?

When pitted against an LAPD crime analyst over a six-month pilot, Brantingham says they found PredPol doubles the accuracy and predicts crime twice as accurately as the crime map. “It’s not because the crime analyst isn’t capable, it’s that the algorithms can pick up those intermediate hot spots.”

“What that says to me as a manager is that I can put my analyst on something else,” Malinowski says. “I don’t need him assigning missions.” That analyst could be used to build intelligence on a drug network or some other larger problem plaguing the city.

The success of the programs in Santa Cruz and Los Angeles has generated the interest of approximately 200 police departments across the nation, says Brantingham. He adds he believes predictive policing is the wave of the future and is not intended to eliminate jobs.

“It is not designed to take the officer out of the equation. There is no replacement for a police officer’s knowledge and skills,” he says. “It’s about putting them in the right place at the right time to prevent crime.”

Ronnie Wendt | Owner/Writer, In Good Company Communications

Ronnie Wendt is a freelance writer based in Waukesha, Wis. She has written about law enforcement and security since 1995.